#56 Around the Campfire; Chopping Down the Wilderness Act

©2013 by Dave Foreman

Next year will be the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Wilderness Act and we will mark it with merrymaking and wingdings all over the United States. The big national celebration will be in Albuquerque in October, and I am most happy that Terry Tempest Williams and I will be among the keynote speakers.

When we raise a bubbly flute to those who gave us the Wilderness Act, we should keep in mind that the brass of both the U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service fought the Wilderness Act every step of the way. Even after the Wilderness Act became the law of the land, the Forest Service still saw it as a mistake and did what they could to undercut it and to keep as much of “their land” as they could out of Wilderness. Though conservation clubs and the Forest Service had become more and more at odds since the end of World War Two, the new Wilderness law made things worse because both sides saw the other as working to wreck Wilderness Areas. Let’s take a look at this now-little-recalled chapter in wilderness history.

The Wilderness Act at once named all National Forest Wilderness and Wild Areas as Wilderness Areas in the congressionally overseen National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). The Forest Service was directed to get the studies done on its last Primitive Areas and send recommendations to Congress by 1974. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Forest Service had set aside a Stetson-full of poorly protected and rather ill-defined Primitive Areas, but then in 1939, new regulations from the Washington office told forest supervisors to better study these areas and draw more thoughtful boundaries. After the recommended boundaries were approved by the Secretary of Agriculture, the areas would be better protected and given the new rank of Wilderness or Wild Areas. (Wilderness Areas if 100,000 acres or more; Wild if under 100,000 acres. The Wilderness Act did away with the cleavage and named them all Wilderness Areas.) The first Wilderness Areas in the NWPS were Forest Service areas already reclassified as Wilderness or Wild. Yet unstudied Primitive Areas were to have recommendations sent to Congress by 1974. Under the Wilderness Act, now only Congress could add or drop areas from the Wilderness System.

Conservation clubs, led by The Wilderness Society (TWS) with help from the Sierra Club, organized across fifty states to implement the Act. Clif Merritt, Ernie Dickerman, and Stewart Brandborg of TWS were bulldogs for grassroots mobilizing, while Harry Crandell was a bloodhound at smelling out what the agencies and Congress were up to. It is through their foresight that a mighty wilderness tide came in by the 1970s. (Until 1979, the leaders of The Wilderness Society were fully bound to finding, training, and empowering independent grassroots wilderness clubs and activists. Brandborg and the others believed wholeheartedly that such a path was the right way to go, even though some leaders of the Sierra Club wanted a more top-down, insider way.)

All agencies got off to a slow start in their studies. The Forest Service brushed off the wilderness crowd’s backing for big Wilderness, and kept at their game of offering chopped-away Primitive Areas for Wilderness. Overall, lands with trees were shunned and “rocks and ice” got the nod for Wilderness in USFS recommendations. Moreover, the Forest Service offered timber sales for bid and built logging roads along the edges of Primitive Areas so as to keep neighboring roadless lands (de facto wilderness, in the words of conservationists) from being added to new Wilderness Areas. This was a witting sham in the Forest Service’s grab bag of tricks to narrow National Forest acres Congress could designate as Wilderness. East Meadow Creek next to the Gore Range-Eagles Nest Primitive Area north of Vail, Colorado, was the poster child for this underhanded scam. In the 1960s, the White River National Forest drew up plans to log the old-growth firs, spruce, and lodgepole pines of East Meadow Creek. Wilderfolk in Vail were against the timber sale and wanted that acreage in the upcoming Eagles Nest Wilderness Area, which otherwise was jagged and icy high country. They talked to Clif Merritt, Western Regional Director of The Wilderness Society in Denver. Clif, a soft-spoken but steadfast fighter for Wilderness, far-sighted strategist, and matchless organizer, got young lawyer and wilderness lover Tony Ruckel on the job. In April of 1969, going against legal orthodoxy that “the United States cannot be sued without its consent,” Ruckel, with Merritt’s backing, sued on the grounds that the Forest Service’s logging next to the Primitive Area would violate the Wilderness Act’s provision allowing the President to recommend “the addition of any contiguous area of national forest lands predominantly of wilderness value.”

Federal Judge William E. Doyle first let conservationists sue the government and then enjoined the timber sale. Forest Service historian Dennis Roth wrote that Doyle “interpreted the language of the Wilderness Act to mean that the Forest Service must refrain from developing a contiguous area which was potentially of wilderness value until the President and Congress had acted on the agency’s recommendations.” This “Parker Case” was the first judicial decision to shield wilderness.

Please click here to read the entire Campfire.

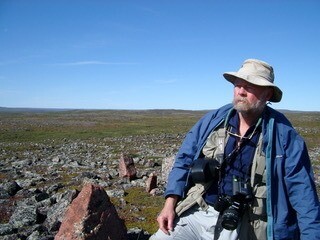

Dave Foreman is the founder of The Rewilding Institute, co-founder of The Wildlands Project and Earth First!, and author of several acclaimed books on wildlands conservation. Books: Rewilding North America | Man Swarm: How Overpopulation Is Killing The WIld World | Take Back Conservation …among several other Rewilding books you can find here. [Photo: Dave Foreman in the barren grounds of Nunavit, Canada © Nancy Morton]