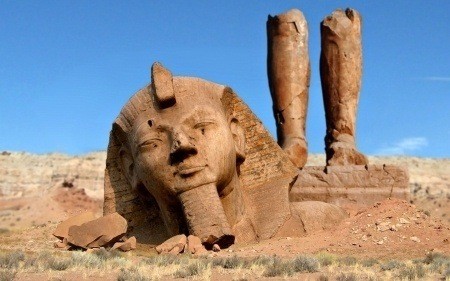

#63 Around the Campfire; The Anthropocene and Ozymandias

Much has been made lately of the so-called Anthropocene—the idea that Homo sapiens has so taken over and modified Earth that we need a new name for our geological age instead of the outmoded Holocene. One remorseless Anthropoceniac writes, “Nature is gone… You are living on a used planet. If this bothers you, get over it. We now live in the Anthropocene—a geological era in which Earth’s atmosphere, lithosphere, and biosphere are shaped primarily by human forces.”

One of the reasons given today for renaming the Anthropocene is that we have so impacted all ecosystems on Earth that there is no “wilderness” left. Insofar as I know, other than babbling about “pristine,” “untouched,” and so forth, none of the Anthropoceniacs ever define what they mean by wilderness, which is not surprising in that none of them give a hint for having been in a Wilderness Area or having studied the citizen wilderness preservation movement.

Moreover, they behave as though their claim about wilderness being snuffed is a new insight of their own. In truth, we wilderness conservationists have been speaking out how Homo sapiens has been wrecking wilderness worldwide for one hundred years. Bob Marshall, a founder of The Wilderness Society, warned eighty years ago that the last wilderness of the Rocky Mountains was “disappearing like a snowbank on a south-facing slope on a warm June day.” Congress said in the 1964 Wilderness Act that the country had to act then due to “increasing population, accompanied by expanding settlement and growing mechanization” or we would leave no lands in a natural condition for future generations. My book, Rewilding North America, documents in gut-wrenching detail how Man has been wreaking a mass extinction for the last 50,000 years or so.

Anthropoceniacs do not seem to understand that when we wilderness conservationists talk about Wilderness Areas we are not playing a mind-game of believing that these are pristine landscapes where the hand of Man has never set foot. Although wilderness holds one end of the human-impact spectrum, it is not a single point but rather a sweep of mostly wild landscapes. Over seventy years ago, Aldo Leopold, the father of the Wilderness Area Idea, wisely wrote that “in any practical program, the unit areas to be preserved must vary greatly in size and in degree of wildness” (emphasis added). Senator Frank Church of Idaho was the bill’s floor manager in 1964 when the Wilderness Act became law. He understood as well as anyone what Congress meant with the wording of the Act. Ten years later, in the heated fight for Wilderness Areas on the Eastern National Forests, when the Forest Service “would have us believe that no lands ever subject to past human impact can qualify as wilderness, now or ever,” Church said, “Nothing could be more contrary to the meaning and intent of the Wilderness Act.” The words pristine and purity are not found in the Wilderness Act, which is the best short explanation of wilderness. It seems that intellectual wilderness naysayers, whether wilderness deconstructionists or Anthropoceniacs, if they look at the Wilderness Act at all, see only the ideal definition of wilderness:

A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.

To continue reading, please click here

Dave Foreman is the founder of The Rewilding Institute, co-founder of The Wildlands Project and Earth First!, and author of several acclaimed books on wildlands conservation. Books: Rewilding North America | Man Swarm: How Overpopulation Is Killing The WIld World | Take Back Conservation …among several other Rewilding books you can find here. [Photo: Dave Foreman in the barren grounds of Nunavit, Canada © Nancy Morton]