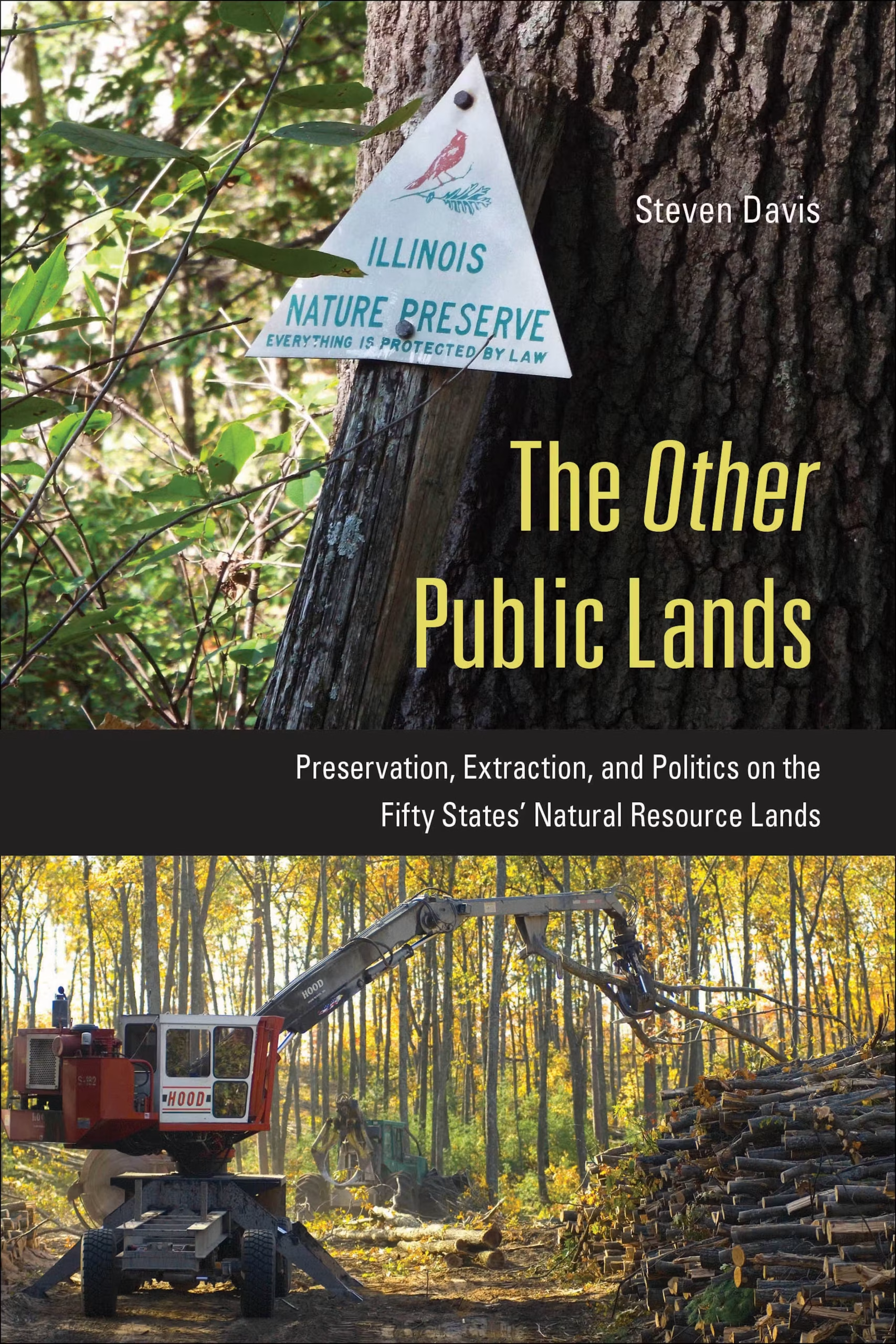

The Other Public Lands: Preservation, Extraction, and Politics on the Fifty States’ Natural Resource Lands

August 14, 2025

Steven Davis, The Other Public Lands: Preservation, Extraction, and Politics on the Fifty States’ Natural Resource Lands. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2025.

Steven Davis is a political scientist and public lands scholar who, in 2018, published In Defense of Public Lands: The Case Against Privatization and Transfer. The subtitle clearly states the case he makes in that book – privatization and transfer of federal lands to states, or sale to private parties, are not good ideas as he explained in considerable detail. As the Trump administration in 2025 enables those who, for three quarters of a century (“Land Grab” of the 1940s, Sagebrush Rebellion, Wise Use Movement), have sought privatization and transfer of federal public lands to states, Davis has published a very timely book. Taken together, these two books reveal why anyone who values federal public lands must rise up in their defense. This book explains state lands, their limitations and values, and makes a clear case that the public should demand more of their state land managers and politicians on behalf of those lands.

The Other Public Lands is most timely because it reveals the limits of state public land management by marshaling extensive history and documentation of the current status of state lands. Davis clearly states his aims in this book: “describe the significant variation between states and regions in how values and priorities get expressed as policy but also look for patterns common to fifty diverse states that distinguish state land management from the federal system.” The book is a description and critique of how states have and are managing their public lands, but also a testimony to the values those lands bring to the citizens of most states.

Davis guides the reader through the complex history and highly variable world of state lands. After a brief history of how states acquired land, a review of the purposes of public land, and patterns of state agency management of those lands, he describes how state public land management began with state parks in the early 1920s. He introduces, in his treatment of state parks, tables that provide a plethora of information about the state systems he is discussing. The “State Park Systems” table for instance lists, as of his writing the book, state park acreages, percentage of state public lands, percentage of total state lands, visits per capita in 2017, whether the park agency is a division of a larger department or stand-alone, and whether there is an entrance fee. With different categories, he presents information in tabular form on acreage and percentage of state-owned natural resource lands (for the 41 states who have them), the level of centralization among state resource agencies, and detailed information on state natural and wilderness areas, state forests and multiple use lands, state wildlife areas, and state trust lands as he describes and analyses them. Davis marshals and efficiently presents a tremendous amount of descriptive information about state lands in these tables, which frees him to analyze historical and contemporary trends and issues involved in each of the state land categories.

In his chapter titled “Appraising State Management of Public Land, subtitled “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly,” he concludes that organization and management of state public lands “are simultaneously quite similar and almost infinitely variable.” Strong across-the-board patterns he finds include “a wildlife management financing regime that strongly privileges game species over general biodiversity, a state park budget process that labors under severe and near-universal constraints, fairly aggressive practices in forest and other resource management to maximize production, and, of course, trust land requirements and practices uniformly imposed (with a few exceptions) by modern legal understandings of the trust doctrine.” There is great variability between states that derives from many factors including history, geography, politics, sociocultural differences, and “including but not limited to, ideology and polarization.”

Presumably Davis undertook the deep and laborious research necessary for The Other Public Lands because he understood that in his previous book he had told only part of the story of American public lands. What if, he must have asked himself, federal lands were transferred to the states, especially in the West where there is so much federal land? How might they handle it? What can be learned from how they have handled the land already under their jurisdiction? He argued persuasively against transfer in the previous book, and his analysis in this one buttresses that case. He explains how federal ownership of land “offers a pretty fantastic deal for states.” For instance, calculating the financial burden shared nationwide for federal lands, it come out to $4 per taxpayer, but if costs of management “were foisted onto just the taxpayers in a handful of relatively lightly populated states where the vast major of federal land is, the burden becomes highly concentrated – for example, a Utah taxpayer’s share would rise to $54.” He concludes, “If states were instead to manage their newly acquired lands as they do state parks for wildlife management areas or even state forests, they would quickly be crushed under an avalanche of management costs in a budgeting context that does not permit deficit spending, unlike the federal government.” And, if they couldn’t cover the costs, what might they do? There is, he concludes, “no reason to believe that they would not proceed to sell them . . . .” The transfer debate is not a “high-minded discussion of the virtues of federalism or local control” but is, his analysis concludes, “driven by an ideologically focused and pointedly political movement to dismantle the federal estate.”

Davis documents how many state legislatures do not seem to value their state lands today as much as state residents do. Many politicians, most in some states, do not perceive or do not accept the values these lands provide state citizens and communities, and do not invest in them as they might and should. Some states, mostly in the far west and northeast, do make the investment and reap the rewards, while other states do not. He concludes that state land managers can learn much from federal managers, if they will, and federal managers can learn from states. This was so, of course, when the federal land management agencies were relatively robust, before the “chainsaw” was unleashed upon them in 2025 by the Trump administration. But the history of successes and failures of federal public land management cannot be erased, so lessons can still be learned. Davis stresses the value of state lands, which are often much more accessible to the public than federal lands. People who are in urban centers or live in the East are far from much of the federal public domain. State public lands “play an outsized role in providing recreation access to wild nature to a diverse array of ordinary people and especially those who lack the wherewithal to travel across the continent to distant national parks because of all kinds of financial, geographic, or cultural barriers.”

Steven Davis has done a great service at this fraught moment in public land history. He has given those of us who use and love public land much to think about and arguments to make against those bent on dismantling the federal public estate. Davis concludes this book on a sobering note. He writes, “A glimpse of the potential of state public lands can be provided, ironically, by looking backward – more than a century back to the time when Progressive Era reformers and conservationists came together to articulate a state park idea that rooted itself in notions of access, democracy, natural integrity, and an intergenerational public interest. While it originally concerned state parks, this stance is actually applicable to all state public lands – specifically, how to find a balance between responsiveness and accessibility on one hand and wise stewardship and restraint necessary to protect a natural system’s integrity on the other. If there is a single theme running through the history of state public lands since that first state parks conference in 2021, it is how far state public land systems have strayed from those founding principles.” This same theme holds for the history of federal lands, and at the moment the federal government seems to be straying rapidly and far from the principles that motivated conservation of public lands of any sort. Davis is not without hope that troublesome trends can be changed, but it will take a huge amount of work.

Got your copy of the book here: The Other Public Lands: Preservation, Extraction, and Politics on the Fifty States’ Natural Resource Lands.

David Brower, then Executive Director of the Sierra Club, gave a talk at Dartmouth College in 1965 on the threat of dams to Grand Canyon National Park. John, a New Hampshire native who had not yet been to the American West, was flabbergasted. “What Can I do?” he asked. Brower handed him a Sierra Club membership application, and he was hooked, his first big conservation issue being establishment of North Cascades National Park.

After grad school at the University of Oregon, John landed in Bellingham, Washington, a month before the park was created. At Western Washington University he was in on the founding of Huxley College of Environmental Studies, teaching environmental education, history, ethics and literature, ultimately serving as dean of the College.

He taught at Huxley for 44 years, climbing and hiking all over the West, especially in the North Cascades, for research and recreation. Author and editor of several books, including Wilderness in National Parks, John served on the board of the National Parks Conservation Association, the Washington Forest Practices Board, and helped found and build the North Cascades Institute.

Retired and now living near Taos, New Mexico, he continues to work for national parks, wilderness, and rewilding the earth.