Caribou Rainforest: From Heartbreak to Hope

All photographs were taken by David Moskowitz. Click here for more.

By David Moskowitz, Braided River, 2018

Introduction by John Miles

Dave Moskowitz is a gifted writer and photographer, a well-informed conservation biologist, a conservation activist, and an indefatigable wilderness traveler. He had to be all of these in order to produce Caribou Rainforest: from Heartbreak to Hope which takes the reader deep into the Caribou Rainforest Ecosystem of northern Idaho, northeastern Washington, and southeastern British Columbia. The book is published by Braided River, an imprint of Mountaineers Books, the goal of which is to combine “photography and writing to bring a fresh perspective to key environmental issues facing western North America’s wildest places” in order promote wilderness preservation and “inspire public action.” The wilderness needing preservation here is slowly giving way to human invasion, primarily logging that is severely eroding habitat of mountain caribou. These beautiful animals may be gone from the United States and are declining in Canada.

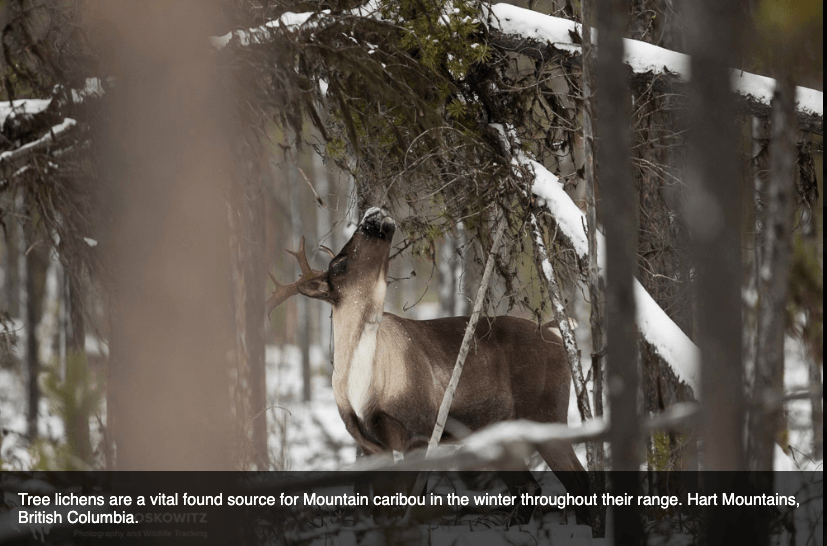

In The Abstract Wild outdoorsman and philosopher Jack Turner wrote, “The necessary work of science produces information but what we need are stories, stories that produce love.” In Caribou Rainforest Moskowitz provides the necessary dose of information, shares stories of travels in search of elusive mountain caribou, and expresses love for this animal and its wild and beautiful home. The excerpt from the book presented here illustrates what a fine writer he is and how effectively he integrates exposition, personal narrative, and heartfelt concern for his subject. Moskowitz can pack much into a sentence, as in “Beautiful in their complexity but tenuous in their nature, creatures like the mountain caribou have built lives carefully strung across the top of an intricate web of ecological relationships.” What an introduction to his explanation of why the mountain caribou, as a specialist species, is in such trouble.

Moskowitz shares stories of the many animals of the Caribou Rainforest, stories of his adventures trying to capture images that would convey the nature of the place, and stories of its people. First peoples, settler colonialism, modern industrial logging, and the plight of marginal rural communities dependent on the logging are all part of the story of the mountain caribou. Society’s relationship to the natural world is always fraught, as it certainly is in the habitat of the mountain caribou: “On the one hand, there is a strong desire to protect, preserve, and enjoy the natural heritage that creates a sense of identity for the people of this region. On the other, there is a real need to earn an income and survive in the modern world through work that often contributes to the behaviors degrading the region.” The “Hope” of the book’s subtitle emerges in the chapter titled “Human Dimensions: The Language of a Landscape.” He expresses hope in the conclusion to this chapter: “Despite all of the destruction it has wrought, modern civilization has demonstrated a huge creative capacity to learn, change, and grow. We have the power to chart a different way forward.” But will we do so, and if we do not, the fate of the mountain caribou will be sealed.

The photographs in Caribou Rainforest are stunning, the product of much time, patience, technical expertise, knowledge of the subject, and suffering (he mentions that “the best way to find mountain caribou in the summer is to look at a map and pick the place you think will have the worst mosquitos…” For one photo, for instance, the caption reads “A grizzly bear pads across a wet subalpine meadow in the Selkirk Mountains.” No mosquitos can be seen, but a wet meadow in summer is one of their favorite places, though given the proximity and demeanor of the bear, he may have gotten this one with a camera trap. All I can say is that all of the hard-won photos in this book are exceptional and selected carefully to complement the text. Viewing the photos is enjoyable, but careful reading of the extensive and excellent text is most rewarding.

Caribou Rainforest is important to rewilders for several reasons. First, it alerts us to the plight of a very endangered species and the need and opportunity to protect a still relatively wild piece of the planet. Second, it illustrates how art and science should come together to reach a public unaware of the story of the values and beauty that is being lost with the possible extinction of a magnificent animal. Third, the approach of the publisher, Braided River, in producing very high quality, attractive books combining the arts of photography and good writing for a general audience is instructive. While the story this book tells is both sad and inspirational, it is told in a very live, engaging, and positive way. Reading and viewing it is an instructive and pleasurable experience. We have much to learn from the book and the way the story is told.

About the Author:

A professional wildlife tracker, photographer, and educator based in northcentral Washington State, DAVID MOSKOWITZ is the photographer and author of two other books, Wildlife of the Pacific Northwest and Wolves in the Land of Salmon. His photography and writing have appeared in numerous other books and publications. David holds a bachelor’s degree in environmental studies and outdoor education from Prescott College. Certified as a track and sign specialist, trailing specialist, and senior tracker through CyberTracker Conservation, he is an evaluator for this rigorous international professional certification program.

David has contributed his technical expertise to a wide variety of wildlife studies regionally, focusing on using tracking and other noninvasive methods to study wildlife ecology and promote conservation. He helped establish the Citizen Wildlife Monitoring Project, a citizen science effort to search for and monitor rare and sensitive wildlife in the Pacific Northwest. Find out more about David’s work at www.DavidMoskowitz.net.

In 2015 David founded the Mountain Caribou Initiative, a visual storytelling project that highlights conservation challenges and opportunities in the Caribou Rainforest. He also produced the documentary film Last Stand: The Vanishing Caribou Rainforest. Images, video, and reporting from this project have appeared in print, digital, and broadcast media in North America and Europe. Learn more at www.CaribouRainforest.org. Photos available for you here (all photos by David Moskowitz):

“Excerpted with permission from Caribou Rainforest: From Heartbreak to Hope (Braided River, November 2018) by David Moskowitz.”

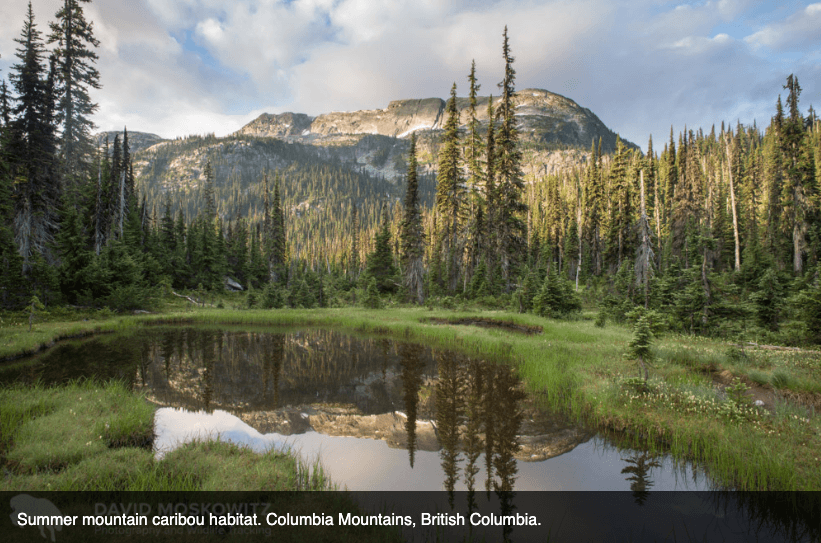

MOUNTAIN CARIBOU ROAM up and down the mountains from valley bottom to mountaintop, back and forth across an international border, in and out of political discourse, and through the history and dreams of people in this region. The forests of these mountains, epic in scale, are home to an assemblage of species found in northern boreal landscapes, coastal rainforests, and the temperate intermontane forests that stretch along mountain ranges across the western United States and Canada. Weather in the region blankets the mountains with coastal moisture and continental chill.

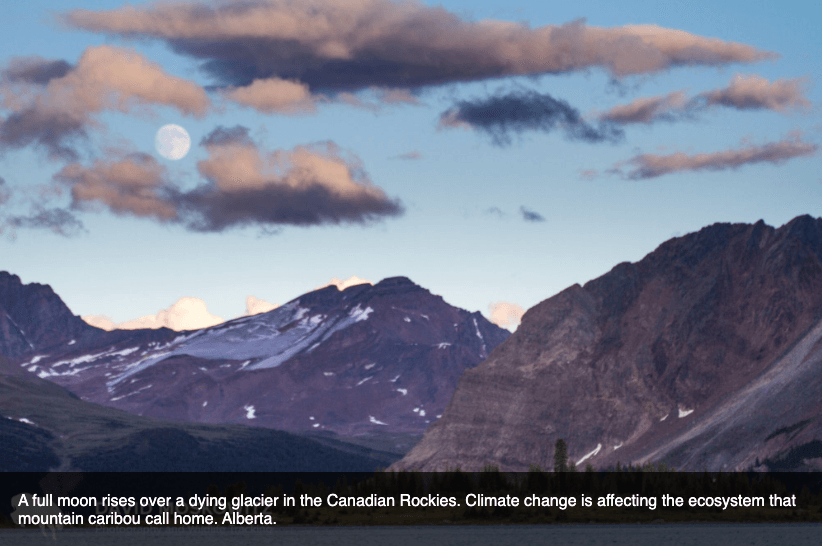

To fully appreciate this story, we must understand the history of how this ecosystem has evolved since the end of the last ice age as well as explore predictions for how it will continue to evolve as the climate changes. We must travel through the traditional territories of numerous indigenous communities and across international boundaries with conservation laws that govern each side. We need to understand the variety of cultural values and experiences of the first peoples of the land and examine the colonial culture of people of European descent, now divided across economic and geographic lines.

Sorting out how to protect this region and heal the wounds inflicted on it since European colonization involves yet another exploration of a shifting landscape of conservation theory from traditional single-species approaches (as laid out in the Endangered Species Act in the United States and in the Species at Risk Act in Canada) to unfolding concepts around ecosystem management. This process involves questioning classic habitat protection models, where the standard has typically been setting aside land as wilderness of one sort or another. Instead we might explore new ideas about nurturing resilience in natural systems for which further human intervention might be useful in the face of the coming impacts of climate change. Like the web of relationships that helped create the mountain caribou’s fragile ecological niche, some of the options for protecting this landscape are complicated and counterintuitive, even seemingly contradictory at times.

THE CURRENT SOUTHERN EDGE of mountain caribou populations can be found along the United States–Canada border in the Selkirk Mountains. Mountain caribou once roamed the peaks and forests of what is now Glacier National Park in northwestern Montana and the mountain ranges to its south and west. Early colonial records of the region document caribou in the mountains of central Idaho, but they have not been recorded there in the past sixty years. For well over a century their numbers have been dwindling, as they have retreated north from their historical range in the western United States. Precise historical population levels are impossible to pin down, but for the past fifty years the trend has been a marked decline. Now fewer than 1,300 mountain caribou remain across their current range, according to the BC Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations, and Rural Development. Separated by rugged geography and habitat fragmentation, the population is further divided into subpopulations that have no contact with one another, making them even more vulnerable to disappearing.

The rainforest itself has also dwindled in the past century. The western slope of the Rocky Mountains in Glacier National Park, Montana, still contains beautiful old stands of cedar and hemlock trees protected within the park boundaries. Heading west from there in the United States, old-growth rainforest persists in patches, now fragmented by development, industrial logging operations, and sprawling open-pit mines.

To the north, where mountain caribou and the interior temperate rainforest reach the zenith of their existence, a similar story unfolds. In the Selkirk Mountains, ongoing logging creeps up to the edges of Glacier National Park, British Columbia, leaving a shrinking island of uncut rainforest too small to protect mountain caribou and the particular ecosystem they depend on.

At an ever-increasing rate, contemporary Canadian and American society’s quixotic quest for capitalistic profit has unraveled this ecosystem’s intricate web of relationships, a story played out many times over across the world. Beyond the possible demise of these mountain caribou and this magnificent rainforest-clad mountain region, there are far-reaching lessons for conservation on a global scale. The failing attempts to turn the tide for this ecosystem, and the wildlife and humans that depend on it, is a modern conservation parable. It sheds light on the increasingly complex human impacts on landscapes, even in our most cherished parks and most distant corners of the planet.

Thousands of miles from the continent’s decision-making capitals, hundreds of miles from any major cities, North America’s inland rainforest beckons us to revel in its untamed beauty. Whether the story of mountain caribou will be recorded as yet another environmental tragedy of our time or instead become a case study for rebuilding resilient ecosystems will depend on our generation’s will to act decisively.

MY OWN EXPERIENCES in the Caribou Rainforest Ecosystem have spanned most of my adult life. My earliest encounters with the region, twenty years ago, were driven by a personal love of adventure and a fervent desire to immerse myself in wild places. Later I returned as a student of the region’s natural history, and finally now as an advocate for its conservation.

For me, the journey to track mountain caribou became a quest to understand something much larger about humankind’s relationship with the world around us, and a personal reckoning with a society seemingly headed down a dark path toward ecological catastrophe. Some experts believe that much of the current population of mountain caribou is doomed. Indeed, conservation ecologist Greg Utzig explained to me how the entire inland rainforest ecosystem is in the process of disintegrating in the face of continued resource extraction and the specter of climate change. Similar assessments are coming in from every corner of the planet from the people who spend their lives looking deeply into the prospects of the world’s natural systems. On a practical level, how do we reconcile the needs of an ever-increasing human population with the finite resources of the planet? On a personal level, in the face of seemingly insurmountable global forces, how does an individual spend each day trying to turn the tide of these forces?

In that first dawn encounter, the magnificent mountain caribou locked eyes with me briefly. I thought of the role he unknowingly now plays in the world. I wondered, what messages from the forest and mountains does this caribou have for us humans? Thousands of square miles of protected forests hang in the balance, dependent on his life or death. In an interview, Chris Ritchie, the head of caribou conservation for the province of British Columbia, made it clear that if these caribou disappear, the forests set aside for them will go back on the chopping block, barring some new justification for their protection. In the United States, should caribou go extinct, critical habitat protections for them will no doubt be lifted. I considered the mounting threats the caribou and his offspring will face as the ecosystem shifts under their feet.

Looking at this caribou, the biologist in me sees an animal assessing an unfamiliar part of the landscape and a potential hazard. The photographer and visual storyteller in me see a powerful creature set in the context of the high-elevation forest it calls home. The part of me experiencing the primal thrill of contact with a large and elusive mammal sees a piece of my own species’ evolution. As a conservationist, I see how this grand evolutionary experiment could end, and how fragile the future of this rare animal and rainforest is.

As I have sought to unravel this story, to bring the mysteries of these rugged and remote mountains down from the heights and out of the dark forest, I have looked into the eyes of many wild creatures, sat on mountaintops taking in the world, and felt the rain and snow sift through the high branches of ancient rainforest trees. I have also looked into the eyes of many people and listened to their stories and experiences of this land, heard their grief, concerns, aspirations, and hopes for what lies ahead for us.

Like the complex tangle of ecological relationships that defines the ecosystem itself, the human experience is similarly complex and beautiful. We must grapple with how to meet our needs while ensuring a reasonable existence for all future generations. The human communities of this place, like the caribou and the grizzly bear, the ancient cedars and glacier-carved peaks, are manifestations of this place. As such, this is their story as well.

WHAT IF A MOUNTAIN CARIBOU wasn’t an object, a type of animal classified discretely, that you could pick up and move from one place to another and have it still be what it was originally? That’s not how we typically think about animals. If you take your family dog on a road trip from Florida to the Yukon, it is still fundamentally the same creature you started the journey with. Your dog is your dog, whether on the beach in Florida or in the forests of the Yukon. In this book, we need to step out of this mode of understanding our reality and into a very different way of perceiving the world.

In complicated ecosystems, characteristics arise from the relationships among the constituent parts. Nothing about a body of water causes it to ebb and flow, yet out of the relationship between the oceans, the moon, and our moving planet arise the tides. If you disrupt the relationships, these characteristics will change, perhaps even disappear. The large temperature difference at the equator and at the poles causes the massive currents in our oceans, which set the stage for our planet’s rich marine ecosystems. But at other times in the globe’s history, these currents did not exist and the oceans were far less biologically rich. As systems evolve, new elements are introduced, others fade away, the interactions among the parts evolve, and these emergent characteristics change. Let’s consider the forests, wildlife, and even human cultures of the Caribou Rainforest within the ecological context that gave rise to them.

THE INLAND TEMPERATE RAINFOREST is much more than a collection of trees. It is the product of an unfathomable number and variety of interactions among the geography, climate, and constituent species found there. As this rainforest grew, in places its own mass influenced the conditions within it, and it created microclimates conducive to life for its inhabitants. In turn, the amazing life history of animals like the mountain caribou arose out of this complex network of relationships. If you take a mountain caribou out of these mountains and put it in a zoo, you will not have captured a mountain caribou. What makes this animal special is the context in which it carries out its life and the web of interactions that make that life possible—and so, too, for the countless other plants and animals that call this region home.

The same can be said about the humans of this landscape. Western civilization has worked hard to perpetuate a myth that our species is somehow separate or different from every other species on the planet. But when we entertain the thought that perhaps our lives, our cultures, even the choices we make are driven by the environment we find ourselves in and our relationships, we realize that, like the mountain caribou and the rainforest, we are elements of a system far larger and more complex than we can grasp.

The challenges we face in the modern world do not end with the protection of distant places and iconic species. My intention is for this book to be one of self-discovery for my kin, humans. The journey begins by understanding the largest of contexts for this ecosystem—the geology, geography, and climatic influences upon which all else has been built. From this foundation the forest evolved. And beyond this came the wild creatures that inhabit this tapestry of mountains and forests. With that as the preamble, we can once again turn back to our own kind and perhaps understand ourselves and our place in the world from a fresh perspective.

I believe our love of exploration and experimentation are two of our species’ most powerful characteristics. In the pages that follow, I have tried to illuminate this magical rainforest landscape and give voice and view to the diversity of life struggling to survive there. A brief encounter with a mother caribou and her calf, or a mother wolf and her pup, and it becomes clear that one characteristic we share with all living creatures is an innate passion and concern for future generations. Let this book be an exploration of a fascinating, complex, and beautiful world, a review of our experiments as a species within it, and a starting point for conversations about how to care for future generations of all the living creatures of the Caribou Rainforest and the world beyond. We can learn valuable lessons from these mountains, forests, creatures, and people.

__________________________

David Moskowitz works as a biologist, photographer, and outdoor educator. He is the author of Wildlife of the Pacific Northwest and Wolves in the Land of Salmon. He has contributed to a wide variety of wildlife studies in western North America, focusing on using tracking and other non-invasive methods to study wildlife ecology and promote conservation. David’s extensive experience includes training mountaineering instructors for Outward Bound, leading wilderness expeditions throughout the western United States and in Alaska, teaching natural history seminars, and as the lead instructor for wildlife programs at Wilderness Awareness School. He lives in Winthrop, Washington.