Rewilding the Po River Basin

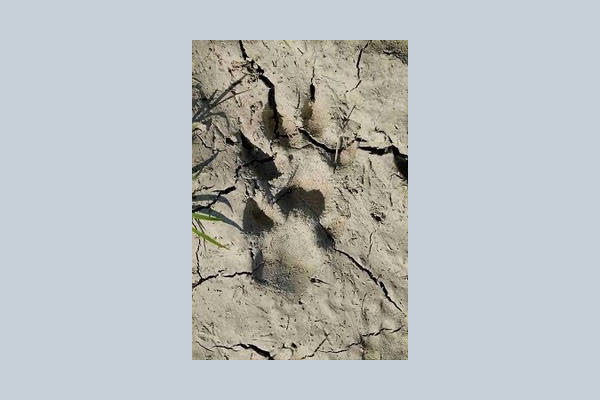

Featured Image: Wolf track in the Po © Giuseppi Moretti

By Giuseppe Moretti

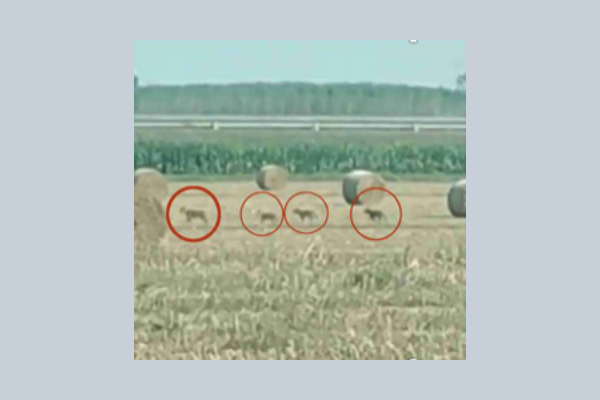

“The wolf in the Po Valley. Incredible to say but it seems true.” Saying that is the mayor of San Daniele Po, Davide Persico. He is also a paleontologist at the University of Parma and founder of the Paleoanthropological Museum of the Po in the municipality he administers. A family of five wolves (two adults and three puppies) was filmed by a farmer last year in the countryside between Roccabianca and San Daniele Po in the Cremona area, revealing to public opinion the presence of this super predator (the video is available on Youtube digiting: “Il lupo delle golene del Po”). “They were already there for some years, but we never revealed it, for fear of creating apprehension in people”, comments Persico, who at least since 2014 has detected the signs of them in the floodplains of the Po.

The wolves’ return is part of the spontaneous phenomenon of rewilding of the Po Valley, in northern Italy’s Padan Plain, which began with the return of the red fox in the 1980s-90s and the roe deer in the early 2000s. In more recent years wild boar have also been sighted. These ungulates, deer, and boar, arrived in the floodplains and neighboring areas of the Po along the natural corridors of its many Apennine and Alpine tributaries. The factors that presumably triggered and favored the phenomenon are to be found in the robust health and numbers of the mountain populations of these wide-ranging mammals. Bold individuals searched for new territories, not only nearby but also in the farthest plain. They found a reasonably quiet natural habitat in the Po floodplain.

© Giuseppi Moretti

To those who still cannot believe in the wolf’s return in the super populated and industry filled Po Valley, Persico repeats the old adage “the predators follow the prey, and being one of the main predators of roe deer and wild boar, he followed their spoor along the riverbanks until he reached them in the floodplains of the great river.” Obviously, the great unknown remains whether this return is only a casual event or whether it will materialize in a stable presence. In the latter case, it would be illusory to think that these animals would limit themselves to the floodplain areas only. The Padan Plain reality is well known: a dense network of urban centers, a high concentration of industrial production units, one of the most modern road / railway / highway connections in Italy. Even the countryside here is intensely cultivated and ecologically reduced to a minimum, further reducing the chances for a predator like the wolf to maintain a stable and organized presence.

The return of the roe deer still seems miraculous, unimaginable only a few decades ago. But there is a factor that diverges from the past and that will probably play in favor of the wolf and all the possible returnees, and it is a lower anthropic pressure. The kind of peasant of the past doesn’t exist any more — apart from the small but constantly growing number of the new bioregional re-inhabitants who practice an organic, biodynamic and permaculture based agriculture … These bioregional reinhabitants can legitimately aspire to take the place of the peasant of the past, but with a new awareness of the importance to operate in and maintain a living and ecologically diversified country. The traditional peasant with his/her assiduous, wide-ranging and competent knowledge traversed their land every day. Each ravine, bank, wetland, stream, and grove was traversed, sieved, and probed in search of food to bring to the table or material to make useful objects and tools, depriving the wildlife of the necessary quiet, undisturbed space to reproduce and thrive. Almost everywhere the human footprint on the rural territory was represented by a large family unit density, and then almost every peasant family had a member or two who was also a hunter, out of necessity. Then there weren’t the large supermarket chains of today, full of cheap food. Field work required a large amount of manual labor to make hay and harvest wheat or corn, not to mention harvest grapes. On average, each farm had eight to ten people working on the fields every day. In the 1950s, a farmer needed 30 hours of work to mow one hectare of alfalfa with a hay sickle by hand (which is why they worked as a team, to finish the job in a reasonable time). Today, with modern technologies, a worker with air-conditioned tractor mows 22 hectares per hour, practically the work of 600 old-time farmers (see the source of this reference here).

These are the facts. In any case, the numbers are modest for now: the wolf family of the video and a few wandering individuals exist in a very large territory. What is certain is that if the presence of the wolf persists and stable packs are formed, then there will be protests, controversies, and conflicts between those who fear for their animals and their personal safety and those who are ready to make barricades to defend the wolf. In between there should be the common sense of a mature culture that knows nature. A common sense which is not present. Yet this would be a terrific opportunity to make an attempt to correct ourselves, grow, and finally learn how to be in the world. Because the world does not belong to us; the world belongs to nature, everyone’s home.

Giuseppe Moretti is a bioregional leader and wildlife proponent in northern Italy. He was introduced to Rewilding Earth by poet Gary Lawless. He thanks Rocco G. Jaconis for revising his translation of this essay.

__________________________

Giuseppe Moretti is a bioregional leader and wildlife proponent in northern Italy.