Where Grizzlies Still Roam and Where They Once Did: Alaska Wilderness versus California Wilderness

Featured Image: The author, in rain gear and hip waders, observing a bald eagle take flight from a misty tidal meadow on Ford Arm, Chichagof Island, Alaska, 1982.

“The Last Frontier”

To camp and work for months during salmon spawning season at a remote “enumeration” weir in Alaska, counting returning Pacific salmon, is to live in close proximity with Ursus arctos, the formidable grizzly or brown bear, in the taxonomic order Carnivora.

Indeed, the job advertisement from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG) in the Juneau Empire read:

This position is stationed for several months in a remote field camp with few or no opportunities to return to town. Poorly heated tents, rainy, wet weather, floods, working on weirs in flood conditions, working in cold water with a wetsuit and snorkel, handling and tagging adult salmon, occasional heavy lifting of weir materials, biting insects, and occasional contact with brown and black bears are all involved.

It was every field biologist and wilderness adventurer’s dream job – getting paid to live in a tent in nearly pristine wilderness and collect field data vital to sustainably managing a key living natural resource. I was exhilarated to be selected for the position.

As I would learn firsthand, that “occasional contact” with brown bears mentioned in the ad was to mean almost daily encounters that could last for hours — moments filled with high drama, wonder, amusement, nerves, or raw fear, sometimes all of the above in quick succession. And at distances measured in mere feet, to yes, sometimes even just inches.

It was our mutual interest in a shared food resource — abundant runs of tasty, nutritious wild Pacific salmon — that brought these two temperamental apex predators together.

In a matter of weeks I was aboard a gear-packed, dependable Beaver with floats (a floatplane) bound for the West Chichagof-Yakobi Wilderness in the Tongass National Forest (the nation’s largest national forest) on outer Chichagof Island, some 80 miles southwest of Juneau on the conifer-cloaked Alexander Archipelago, or Alaska Panhandle. It was a bumpy, noisy ride.

Typical raincoast weather prevailed: rain squalls splattering the Beaver’s window panes and heavy gray clouds. At one point we’d been seemingly suspended in a blank white void for some minutes, buffeted by the headwinds, the engine blaring.

Suddenly we burst into the open. A hundred feet below was a rugged ridge above timberline and carpeted with verdant alpine meadow. There, loping through the grasses and blueberries, startled by our sudden intrusion, was a hefty brown bear, knotted muscles rippling through its shaggy coat with each stride. It seemed a premonition that we should see our first grizzly bear even before we reached our destination. And that premonition proved accurate.

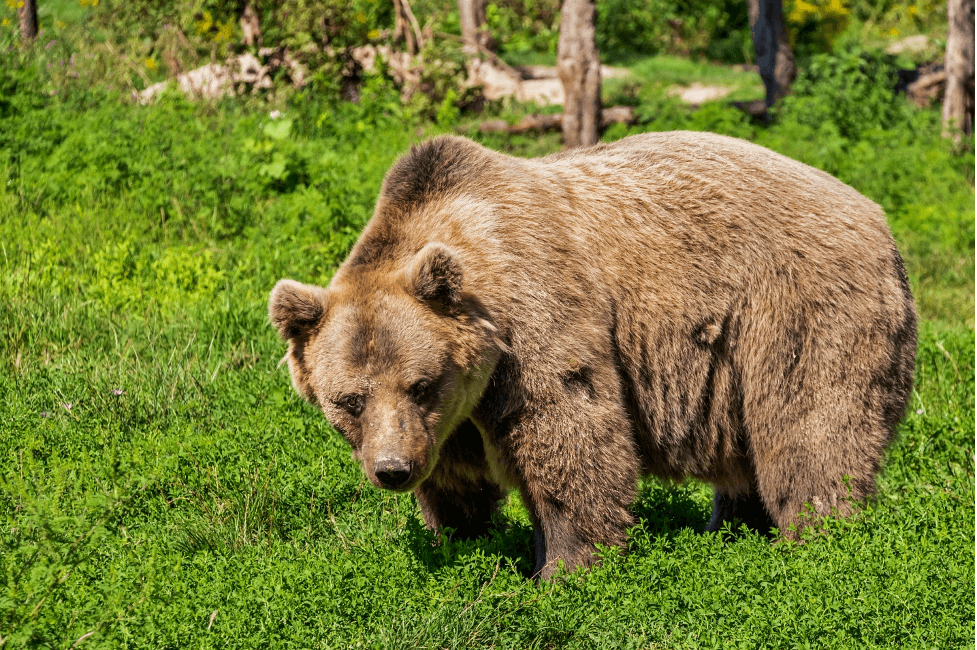

Grizzly Bear (Source: Robert Balog on Pixabay)

As a naked, scrawny ape in the taxonomic order Primates – lacking the claws, jaws, canines, and brute size and strength of this particular (omnivorous) carnivore – I was instinctively commanded by the powerful grizzly’s close proximity.

Not infrequently, in these daily close encounters, far from any rescuer if something were to go amiss, I felt the bears provoke in me something far more intense than mere attention: raw, visceral dread, a primordial fear that fogged my brain, froze my fingers, and enfeebled my knees. We human overlords in the comfortable, complacent era of Homo industrialis and H. colossus are not used to having our unquestioned authority challenged by these furry beasts. They hail from a bygone era in prehistory, from a time when our ancient ancestors sought protection huddled beside flickering Pleistocene campfires, or sheltering and shivering in damp, cold caves.

Never far from my mind was the realization that several colleagues of mine in ADFG had been charged at close range, encounters that did not end well. One ADFG fisheries technician who had been counting spawning salmon on a stream near Yakutat, accompanied by his faithful, experienced dog Rex, a Siberian husky/black Lab mix, was charged by a sow with cubs one day who had mistaken him for a boar (male). As he fumbled with his holstered sidearm, his courageous hound Rex (“the dog who forgot to fear”) lunged at the threatening sow standing on her hind legs ten feet away. The she-bear savagely crushed and bit Rex to death but then turned and took off. (This harrowing episode was described in an August 1976 account in Outdoor Life magazine.)

And I personally knew folks who’d been, in the indelicate words of one of my bosses, “chewed on” by grizzly bears, fortunately none to the point of permanent disfigurement or disability. But it weighs on you.

Human hand (of a six-foot ADFG friend of mine) and brown bear paw and claws.

One night, the tranquility of my canvas tent was shattered by a bloodcurdling cacophony of deep roars, grunts, and growls outside, down by the salmon stream some thirty yards away, all too close for comfort. Unable to withstand the suspense, I slipped into my hip waders, grabbed a lantern and flashlight, and tightly gripped my 12-gauge shotgun just in case. Then I stepped out of the relative coziness of the lantern-lit tent and into the gloomy night, darker yet for the dense canopy of ancient, interlocking Sitka spruces and western hemlocks towering overhead.

I walked anxiously toward the gurgling watercourse and the piercing bellows. At least they came from the opposite side of the stream – a bit more of a buffer in any onslaught. Shining my flashlight in that direction, I saw two sets of bright orange eyes glaring vividly back at me from the blackness of the opposing streambank. Then one set of eyes blinked out as that bear turned to face its adversary. An instant later, it roared like a lion, and then charged its foe, judging from the sound of crashing foliage and snapping branches.

Satisfied that my partner and I were not the target of these combative bellows, I turned back toward my beckoning tent, knowing full well that its thin canvas fabric provided scant protection from any 5-inch claws that meant business. That night, like many others, I slept fitfully with loaded gun by my side. (And this wasn’t even the night that I heard a bear’s claw scrape along the tent canvas inches from my head.)

Yet just before I left the streambank, my gaze darted upward, and suddenly I caught sight of the aurora borealis, those northern lights of Arctic legend, dancing sublimely and silently. Ribbons and curtains of exalted, ethereal green light swayed and twisted silently in the starry heavens, as charged particles riding the solar wind were deflected by the Earth’s magnetic field and collided with excited molecules in the upper atmosphere. This celestial spectacle was aloof, utterly indifferent to one observant, appreciative human and two oblivious grizzly bears clashing over fishing rights.

Northern lights (Source: David Mark on Pixabay)

I stood for a while, shivering but enchanted by the majestic spectacle of the aurora and the two grumpy brown bears rumbling across the stream. And I thought to myself, this is quintessential Alaska. This is authentic wilderness.

“The (Once) Golden Bear State”

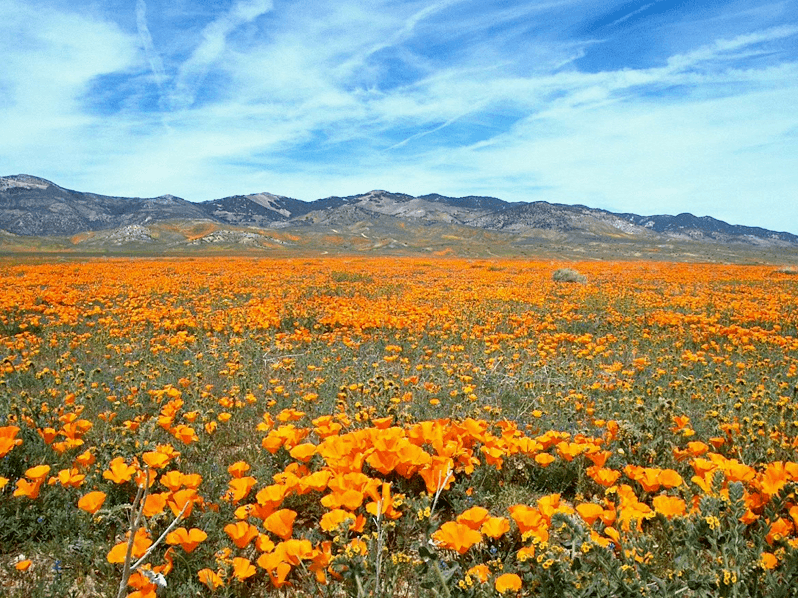

Geographically, geologically, and ecologically, California is a truly land of superlatives. It boasts the world’s tallest tree (California redwood), the world’s largest tree (giant sequoia), the world’s oldest tree (bristlecone pine), the highest point in the 48 contiguous states (Mt. Whitney at 14,505 ft.), and the lowest point in all of North America at the Badwater Basin in Death Valley (280 feet below sea level). I have been to and reveled in all of these wonders but for the bristlecone pine stands in the isolated White Mountains east of the Sierra Nevada.

California gave birth to the wilderness conservation movement in 1892 with the founding of the Sierra Club in San Francisco by John Muir and his conservation compatriots. Today, there are about 150 wilderness areas in the state, the largest in Death Valley National Park at 3.1 million acres. In total, they encompass nearly 15 million acres – about 15 percent of California. It’s a pittance by the lofty standards of Alaska – which enjoys eight of the ten largest units of the National Wilderness Preservation System – but it’s still something to be proud of and thankful for.

California is globally recognized as one of the Earth’s “biologically diverse hotspots.” This is a function of both its rich biodiversity and the number of imperiled species and subspecies within its borders, which surpass those of any other state.

As the California Academy of Sciences notes: “unique habitats have produced a rich mosaic of life. Many plants and animals here are found nowhere else [i.e., endemic], making California one of the most biologically diverse places in the world.” Unfortunately, the Academy emphasizes, “some of the most spectacular places on earth are also the most threatened.” As far and away the most populous state, the protection of California’s unique biodiversity is a daunting challenge.

California poppies (Eschscholzia californica) blooming in all their glory. (Source: Lloyd Waters on Pixabay)

Located in the far north of the Arctic and Subarctic, of course, Alaska doesn’t possess nearly the diversity of flora and fauna that California does, consistent with global patterns of declining biodiversity (species abundance) from the tropics to the poles.

A decade after my Alaskan experiences, by then living and working as an environmental planner in Southern California, I used to give many slide shows about Alaska to school classes, Boy Scout troops, REI, Patagonia, and North Face audiences, and a number of Sierra Club and Audubon groups and chapters. For me it was a chance to reminiscence and to share my love for the wild beauty of the “last frontier” with appreciative audiences, who ate it up.

Of course, these slide shows featured wild salmon, grizzly and black bears, bald eagles galore, orcas and humpback whales, glaciers, old-growth forest, crystalline streams, soaring mountain peaks, smoking volcanoes in the Aleutian chain, and untrammeled wilderness.

Yet they also featured something else less edifying: human population pressures on the natural world. In fact, I started every presentation with a dramatic comparison and contrast between California and Alaska. California, the third largest state in the union by land area, is only a fourth the size of immense Alaska. However, California then had a population of about 30 million compared to Alaska’s one-half million; that is, its population was 60 times larger than Alaska’s, and its population density a staggering 240 times greater.

No wonder the two states were so different in so many respects.

California flag

And just to cite one germane example: California had once possessed grizzly bears, massive creatures of yore, the fabled golden bear from which the state derives its nickname. But now, as the sad saying went, the only place this wild symbol could be found in California was on the state flag.

In 1866 a golden bear weighing 2,200 lbs. was shot and killed in San Diego County. This behemoth was exceeded in 1872 by another grizzly weighing 2,320 lbs., killed in what is now northwest Los Angeles County, where 10 million people now reside on terrain where gigantic bears once ambled. Bruins this size could have rested their chins on basketball hoops when standing upright on two legs, which they did when curious or alarmed or angry.

Grizzly bears will often stand on their hind legs when curious, alarmed, or angry.

The very last California grizzly felled in the wild was shot in Tulare County in 1922. In 1924 – almost a century ago – a golden bear that roamed the southern Sierra Nevada was spotted for what turned out to be the last time. Wild grizzlies have never been seen again roaming free in California. Yet thankfully, they endure by the tens of thousands in thinly-populated Alaska and Canada.

But the role of the golden bear as a symbol of California’s pride and might was just beginning. It is the official state animal, appearing on the California flag; it is honored by the names of the sport teams of UC Berkeley (California Golden Bears) and UCLA (Bruins), and it is the mascot of UC-Riverside (Scottie the bear). Hundreds of other honorable mentions abound.

Wild California had been tamed and domesticated. The giant bears were replaced by more and more people, sheep, and cattle. Their habitats and haunts were usurped by ranches, cropland, vineyards, oil wells, reservoirs, and sprawling cities. Water in the streams that once churned with spawning salmon the great bears once gorged on was diverted to thirsty cities and crops to feed the multiplying millions in those cities.

A large omnivore/carnivore like a grizzly bear has a large home range; extensive areas of wildland and suitable habitat are needed for it to survive in large, genetically viable populations.

The upshot: by whatever name it is known, Ursus arctos survives and thrives only in areas with few humans.

As for me, a decade after my experiences with salmon and bears in wild Alaska, I authored a book entitled Where Salmon Come to Die: An Autumn on Alaska’s Raincoast (Pruett Press, Boulder, CO). In its preface, I wrote:

“….here in Southern California, with its crowds, smog, and clogged freeways, I realize all the more poignantly just how unique this [Alaskan] experience was. It seems like it belongs to another century…or another planet.”

“…a few of the brighter stars, such as Sirius and Rigel, manage to pierce the veil of smog and glare that now blights Southern California.”

And in the epilogue:

“Ten years ago [in Alaska], I remember thinking that it would be boring to go hiking anywhere else without brown bears. The constant thrill and threat of a potential grizzly encounter enlivened each hike there. I relished walking close to the edge. Here in California, the forests devoid of grizzlies are safer and more boring to stroll through now. Ironically, as the forests have become tamer and safer, the streets have gotten wilder and more dangerous.”

…

“…the urban wastelands left behind in the stampede of American civilization toward some unattainable promised land of ever-increasing material plenty are more savage than the trampled wilderness they replace.”

More enlightened attitudes toward large carnivores and predators, from eagles and hawks (which as recently as the first half the 20th century were slaughtered en masse as vermin) to cougars, coyotes, and wolves, lend hope to the prospects of rewilding and large-scale ecosystem restoration throughout North America, including large swaths of California.

I am skeptical, though, of the prospects for ever reintroducing the grizzly bear at scale in California, except perhaps in a few remote, sparsely inhabited places – and of its survival in any kind of substantial and self-sustaining numbers. These big bruins simply require too much open space and are too ornery to tolerate the heavy-handed human presence that 40 million human inhabitants and all our appurtenances exert on an overburdened land.

This is why it is important (among many other reasons) that western Canada and Alaska remain thinly populated, so that brown bears and other wild brethren may continue to flourish in these strongholds, over at least part of their ancestral range.

When I first moved to California, my old boss with ADFG, a veteran fishery biologist and fellow lover of wilderness and wildlife, informed me solemnly in writing that “your sacred mission as an environmental planner is to keep California just livable enough that its millions of residents don’t move north!” Alas, I failed miserably in that mission impossible, as Oregonians, Washingtonians, and Idahoans can all attest.

Since 1990 alone, an exodus of more than 13 million Californians has spilled out of this overpopulated, overstressed paradise lost, disgorging multitudes throughout the West, from the deserts to the Rockies and the Cascades. Yet California’s population has continued to swell in spite of this hemorrhaging of humanity, almost entirely due to immigration.

Grizzly bears are the very epitome of the wild – the authentic wild – not the ersatz wild of theme parks or zoos and overcrowded national parks that resemble theme parks and human zoos.

I have often pondered the meaning of Thoreau’s famous aphorism, “In Wildness is the Preservation of the World.” I certainly appreciated wildness like Thoreau did, but I wasn’t quite sure I understood all that he was driving at. I’m still not sure, but now I see that unless industrialized civilization adopts the wisdom and self-restraint needed to preserve large areas as wilderness and large carnivores like the grizzly bear, not only will the wilderness and its wildlife perish, but our civilization as well. Civilizations cannot be built — or long endure — on wastelands.

Editors’ note: The Rewilding Institute acknowledges that population and immigration issues are contentious, but we maintain that human numbers — in terms of both population and consumption — must be compassionately and fairly stabilized and reduced if we are to effectively confront the extinction and climate crises. Please see our Population position statement and other coverage around human population.

Leon Kolankiewicz is Scientific Director of NumbersUSA and Vice-President of Scientists and Environmentalists for Population Stabilization. His career as a wildlife/fisheries biologist and environmental scientist spans more than 30 years, 40 states, and three countries. He has worked for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, Alaska Department Fish and Game, Orange County (California) Environmental Management Agency, as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Honduras, and as an environmental consultant preparing environmental impact statements under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) for more than 10 federal agencies. He is also the author of Where Salmon Come to Die: An Autumn on Alaska’s Raincoast, which New York Times outdoor columnist Nelson Bryant called “a celebration of wilderness.”

Insightful and beautifully written.

Having been raised for the most part in Oregon and Montana, it is always disappointing to return there and see its present state. Human overpopulation is slowly crowding out nature. What used to be small towns in beautiful, open valleys have become victims of sprawl with homes crawling up the valley hillsides. We know that this overpopulation is more than 80% the product of immigration. The failure of our government to enforce immigration law and the drive of those who want cheap labor and depressed wages have caused this. it is depressing.

Thank you for all you do & I’m so sorry for the loss of your dog Rex

Thank you for this wonderfully truthful article that hopefully will shed some light and educate the public on our disappearing Wildlife and wildlands.

Great story about rewilding in the wilds of Alaska. I live in NW Washington and every decade some of us see the wilderness slipping away. Now it’s the beautiful salmon runs. Can you imagine if after calves could head out to a billion acre pasture to feed before returning to the owner’s barn full grown with no roundups, vet bills or hay needed! How would the cattle industry react if this critter was endangered?

Well our salmon is that critter. An animal that feeds not only humans but an entire watershed of other species and now in a flicker of time they are headed to extinction. Yup, Climate change and population growth. Wilderness and the awesome feeling of beauty, peace and our connection to our earth is slipping away. Unfortunately there are billions of us out that are willing to give nature up for a cheap tv and cell phone. How do you get that crowd to fight for the wilderness? 83 and have see many wilderness and areas of earthly beauty swallowed up by population growth.

Absolutely superb column…thanks Leon.

Wonderful. Thank you. So grateful for your courage, and Rewilding’s, for speaking up about population. Leon, I would love to read your thoughts on how we bring this urgent problem to the forefront of current debates.

Thank you for your interest and concern, Susie. And I appreciate your compliment as well. As to your question about the “current debates,” the most salient of those debates concerns the Biden administration’s new immigration bill. According to analysis by NumbersUSA, if passed, over the next decade alone, this radical proposal would legalize and admit a total of 37 million new American residents “on a path to citizenship.” That’s a population almost as large as California’s.

If this comes to pass, it would result in by far the largest single decade of population growth in America’s history, and would also set the stage for far larger population growth rates in subsequent decades; the U.S. population would continue to surge upward with no end in sight. Population pressures on wildlife, wildlands, and wilderness would inevitably intensify.

While elites worship at the altar of endless growth, whether propelled by more babies or more immigrants, rank-and-file Americans of all political stripes and all races and ethnicities do not. They reject this kind of forced population growth and its baleful environmental consequences.

In a survey of 1,500 likely voters conducted by Pulse Opinion Research in May 2020, respondents were asked:

“Over the rest of this century, would you prefer that the nation’s population continue to grow toward 500 million, grow much more slowly, stay about the same as it is now at 331 million, or slowly become smaller?” Only 17% (less than 1 in 5) responded: “Continue to grow toward 500 million.” 43% said “grow much more slowly;” 22% said “stay about the same at 331 million; and 10% said “slowly become smaller.” 8% weren’t sure.

Americans don’t want the gridlock, overcrowding, air and water pollution, water scarcity, carbon emissions, habitat destruction, fossil fuel depletion, and loss of wildlife that accompany perpetual population growth. We need to make sure our politicians hear that loud and clear.