A Talk with Jack Loeffler (Part 1): Indigenous Worldviews, Desert Lessons, Direct Action

I had the good fortune to talk with Jack Loeffler over two days in December of 2021, and I transcribed the conversation. This is part one of an edited version of our talk. (Read part two here and part three here.)

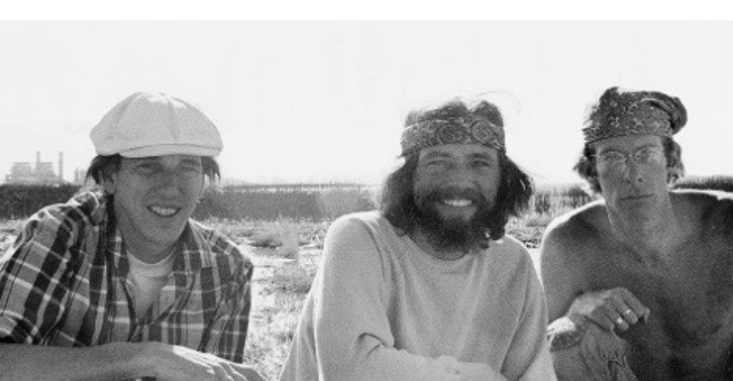

The Black Mesa Defense Fund (from left: Jim Hopper, Jack Loeffler, and Terrence Moore)

Photo by Terrence Moore, 1970.

(Rowan Kilduff) RK: After reading your book Headed into the Wind, I just had so many things I wanted to talk to you about and I would like to transcribe some parts of this, parts of what we will talk about, and add that there, and send to Rewilding Earth also, because they’re a great team.

(Jack Loeffler) JL They’re great.

RK Yeah, and I’d like to reach people to — like you said a couple of times — to help rewild this human consciousness.

JL Yes, actually I also did a podcast for The Rewilding Institute about, oh less than a year ago, and I know Dave Foreman very well. Dave and I go all the way back 50 years to when I was doing the Black Mesa Defense Fund and Dave was helping out with that. And he went on to found Earth First!, and so I interviewed Dave for a radio series I was producing at that time, and that interview is actually in another book I did, actually my first book called Headed Upstream: Interviews with Iconoclasts. And, it wasn’t supposed to be a book, but in 1984 while I was working on the radio series, my wife and I and our daughter were down in Tucson. My close compañero Ed Abbey, was not well and so I was trying to help him, we’d rented out our house here in town, and used the rent money to rent a house down in Tucson. And so I was preparing this radio series and I asked Ed to be the editor of it and to listen to it to just say what he thought, and he listened to the whole series — there were thirteen 30 min. programs, and he listened to the whole thing twice (laughs) and said ‘gee, this should be a book’, and he introduced me to a publisher — that turned into my first book, and very heavily oriented toward environmental thinking, that book. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it —

RK It’s on my list, Jack, it’s on my list!

JL The upshot is that a lot of my close friends are in that book, and then there were a couple of people whom I had met specifically for that book, at least one, and that was Garrett Hardin who wrote the ”Tragedy of the Commons” which I had read in 1970 when we were starting the Black Mesa Defense Fund, and a… I don’t know if you know anything about the Black Mesa Defense Fund but it was sort of one of the first of the radical environmental groups, they called us ‘eco-terrorists’’ —

RK (laughs)

JL — and of course they’re the eco-terrorists (laughs)

RK Jack, you know what I have right here? I have a picture of you, a very young picture of you and it’s ‘’The Black Mesa Defense Fund —Jimmy Hopper, Terence Moore, Jack Loeffler, 1970.’’

JL The Four Corners Power Plant.

RK That’s right. And you wrote there, if I can just quote you back to you — ‘’sitting here as an elder nearly half a century later I still feel that fire in my belly that I felt back then to continue this endless battle that I now recognise as the greatest and most significant battle of our time, the battle to shift the collective attitude beyond an economically dominated culture of practice into an ecologically founded defense-of-habitat-oriented paradigm vital to the future of our biotic community. If this battle fails, so do we as a species.’’ That’s really something.

JL Wow.

RK Those are your words, and how do you feel, looking at it now — how’s that battle going, you know? What’s that kind of activism now, there are a lot of people getting into activism, a lot of the youth moving and what do you feel is the real activism in these times? What’s the activism-to-do?

JL Well, the youth — as I said somewhere in that book — it will take the young people, the children, to save us from ourselves. But I also see certain trends that are very positive and certain trends that are negative. And one of the things that has really caused me great alarm is the divided nature of human consciousness today, and there are those of us who really understand, and have understood probably for much of our lives, how important the flow of nature is and to work with it rather than against it — as a model for working against it I think of the Glen Canyon Dam which dams the Colorado River and subsequently plugs the flow of nature through the South-West, and that’s sort of an image I have in my mind. And so, my own work right now is hopefully oriented mostly to try to get as many of us as possibly to rally around the notion that we are part of the planet not apart from it, and, actually I took a cue from the great poet Robinson Jeffers for that, who, by the way, was one of Gary Snyder’s great teachers. Gary once told me that before he started reading his own poetry in public he would read Jeffers’ poetry. And he has one poem entitled “The Answer” which, my friend David Brower, gee, so many of my friends are gone now — Gary’s still with us, but he’s 91 — but Dave took that one phrase ‘’not man apart’’ to be the title for the publication for Friends of the Earth which he founded back in well, it was happening in 1970 and that’s when I met Dave for the first time. And so I look at all of these different wonderful fellow humans that I’ve gotten to know — some of them very well — including Garret Hardin, by the way, we really ended up becoming friends.

(Note: Jack talked about Hardin’s ‘’Tragedy of the Commons’’ and ‘’An Ecolate View of the Human Predicament’’ in the Rewilding Earth Podcast here.)

And so I started to swing out with the whole notion of what the ‘’commons’’ really means back in 2009/10. My daughter, Peregrina and I met Elinor Ostrom who wrote a magnificent book entitled, Governing the Commons which I have here, and we interviewed her — she got the 2009 Nobel Prize for it, and she took some umbrage at Garrett Hardin because never once in his essay did he mention the word ‘trust’, and so one of the things that she introduced in her book was the notion of polycentric governance of the commons which I have taken to heart.

Now, one thing that I have long shared with both Ed Abbey and Gary Snyder, actually it’s one of the things that sort (laughs) was part of each of our friendships, was the whole notion of anarchist thought. And Ed… I liken Ed to Bakunin and Gary to Kropotkin (laughs). Ah, Ed Bakunin had fought at the barricades and Ed was a true activist — he didn’t just sit there and write at his typewriter, by the way it was a typewriter and not a computer. I have by the way one of his early manuscripts of The Monkey Wrench Gang, typed, here — which is a treasure, for many years it’s the only one I ever read.

RK I bet you have a house full of treasures there, all those recordings.

JL I do, but that’s the problem. I’m 85 years old, Rowan (laughs) and, what do you do with it all? So what I’ve done is I’ve donated what I call my aural (A-U-R-A-L) history archive to the History Museum of New Mexico, at the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe, so that it can be delved into because a lot of it has to do with not just interviews with people like Ed and Gary … and all of those folks, Elinor Ostrom… but also many more recordings of folksongs, traditional songs, and interviews with people from traditional cultures, because early on, way early on, I became captivated with how important what I think of as ‘indigenous mindedness’ really is. And that probably started for me probably 60 years ago at least, when I found myself in a tipi with 5 different Indian tribes represented and I was eating peyote. And we shared that peyote experience, and I became deeply involved from that moment onward in trying to understand different native perspectives that subsequently over the intervening years, I’ve either lived with, or visited deeply with many, many cultures throughout the North American South-West and Mexico. And I’ve had some of the most profound experiences with them, for example, in your note you mentioned something about music, ‘cause I know you’re a musician and — cause I remember you telling me that! (big laughs from both)

RK And just a quick side note before you continue, because this is really interesting for me and one thing I feel we can relate on a lot. I’ve also been really lucky here because a good friend of mine, he’s about 70 years old now, he’s a medicine man, Sundancer about 30 years, and a Peyotero…. so I really, wow, I really got a lot from him and from this friendship and it’s one of the things that really helped me to clear my thinking about things. (laughs)

JL Well, I totally understand.

RK Yeah, yeah, and to get to the heart of things, and see this interconnection and I guess I just jumped from there and went into writing… it was actually after reading part of an interview with Gary Snyder back in the late 60’s or so, I think he was talking about — it’s in his book The Real Work, the collected interviews, it’s my favorite — he was saying something about these experiences that they are just too big to share, to put into words, I guess I’ve been trying to put some of that in there [my in-progress book], how we’re kin, and what can we do — what kind of activism can we do with our friends, family, community, what can we take from that, and live a life well-lived, you know?

JL Beautiful. I want to tell you about this one event which was really profound for me, it was oh, about 15 years ago now. Does the name Gary Nabhan, does the name Gary Paul Nabhan ring a bell?

RK Yeah. I’ve read some of his poetry.

JL Well he’s a really close friend, and he and his wife Laurie Monty and I have spent a fair amount of time together in Seri Indian country on the west coast of Sonora, mainland Mexico but on the Sea of Cortez. They’re very shamanically oriented and I was recording; I had recorded a couple hundred of their songs over the years. Laurie actually did her PhD dissertation on, what I call ‘geo-mythic mapping’ songs of the Seri Indians, which are… intense. But I was recording this one man, Jesus Rojo Montaño who’s a shaman — was — he passed away from COVID within the past year or so, but in his sort of pigeon-spanish he said to me, so I could understand it with my pigeon-spanish, that he wanted to sing the song of the leaf-cutter ant, and the upshot is that it took him about 15-20 seconds and he basically assumed the form of the leaf-cutter ant, sang the song four times and then it took another 15 or 20 seconds for him to return to his human consciousness. And I realised that he knew far more about the leaf-cutter ant than Edward O. Wilson, who was the world’s foremost entomologist, who just died last Sunday by the way, and a person for whom I have enormous respect by the way. And one of the things that Gary mentioned to me, Gary Nabhan, was that he felt that the Seri Indians in particular understood far more deeply, broadly intellectually and intuitively, more about the ecology of their home land than any scientist could ever get. Now I love science, but I feel that it’s an incomplete perspective. I believe that all single perspectives are incomplete.

(RK note: Feynman’s message that the more ways you can think of something the bigger chance to find an answer, or Kip Thorne saying that two ways of explaining how things are can be equivalent, they’re the same laws written in different languages, so there’s no point asking which is right, just which is prettier.)

And that brings up something, in 1995 or 6 I think it was, I had the opportunity to interview Edward O. Wilson, where he teaching at Harvard, ’95 (he’ retired in ’96, I just read) and he had been all over the world working with indigenous peoples, I mean they would guide him into these various very remote places so that he could study the insect life, in particular the ants. And so I finally asked Wilson, oh, he’d written a book called Consilience which I have here… the word itself is an Old English or Medieval word meaning ‘a jumping together of disciplines’ and he was thinking like: biology, physics, the humanities. And I asked him if he could imagine factoring in indigenous perspective into his sense of consilience and that was not something he could understand. And I’ve reflected on that for all of these years, over 25 years now, and that does not lessen him in my own regard for his work, but I realise that each discipline, the more we deeply practice it and thus the discipline itself is opening our minds to try to see within a sphere of reference rather than just a frame of reference, that we really lock ourselves into something. (RK: Bob Thurman calls E.O. Wilson ‘The Ant-Man’.)

–––––––

JL Mike Harner and I met in Big Sur in 1962. Shortly before, two or three months before I moved here to Northern New Mexico where I’ve been all these years, basically. But Mike became a very dear friend, and there was a point where I had be back in California for a few months back in 1964, where Mike invited me to house-sit his apartment while he started his trial-marriage to Sandra Harner, who is still with us and is still a dear friend. There for a month or two every Thursday evening Mike would come by, another man, a Chilean psychiatrist by the name of Claudio Naranjo would come by, and Carlos Castaneda would come by. Carlos was still working on his phD at UCLA, and he hadn’t written his dissertation yet that turned into the Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge, but he talked a lot about Juan Matus, the man, but anyway the four of us would talk about our senses of our psychedelic experiences. Mike just died 3 years ago, and I was there last in Mill Valley, stayed with them — Mike and Sandy — I think it was in 2014, I’d gone into the Bay to interview another scientist: Fritjof Capra, does that name ring a bell?

RK Yes and thanks to you I got back into reading Capra after a long time. You know when I was about 18, I got this great book called Modern Buddhism: Readings for the Unenlightened edited by Donald Lopez, and in there, that set me off on all kinds of things because there were excerpts from — Gary Synder was in there, actually about Black Mesa — a piece he wrote on this, there was Jack Kerouac, Shunryu Suzuki, and Fritjof Capra — a part from the Tao of Physics. And I got so much out of this book and it travelled with me and it took me years to track down all of the full books, and I remember listening to the RE podcast (I listened to it 3 times!) you mentioned A Systems View of Life, the book, and I read it. I got so many good tips from you — from your book and also these interviews, so I jumped off in all directions.

JL Well, Fritjof, he and I met in 1989. He came by my house at one point and I interviewed him then. Ed Abbey just died a few weeks before so my thinking was still very much with Brother Ed, but in 2014 when I read A Systems View of Life, A Unifying Vision I read it twice I was so knocked out by it, and called him up and went back and got a really beautiful interview with him, back in Berkeley. It turns out we discovered that I’m either 2 or 3 years older than he is so we were in that geriatric mode of comparing notes! (both laugh)

RK There’s so much in that book, it’s a big book and covers everything.

JL It does. It’s a beautiful book.

RK And this thinking from Maturana and Varela, this is really something.

JL I have right here, on my big computer, something from Maturana, I’ll read it: “Living systems are cognitive systems and living as a process is a process of cognition, this statement is valid for all organisms with or without a nervous system.” And boy, have I taken that to heart.

I wrote an essay for a publication called LUCA’s dream, LUCA being the acronym for Last Universal Common Ancestor, and I realised that if this is as they think it is, in other words if we indeed share 355 genes with LUCA, everything on this planet that is alive or ever has been since LUCA, is related. There was ostensibly other cells similar to LUCA that didn’t survive but LUCA did and here we are so —

RK I just got a thought, something I’d like to ask you — it’s not on my list of questions but — I don’t even know if I will get to my list of questions — you’re an amazing talker and I love to listen to you. I was thinking, going back to the indigenous worldview and connecting it into this and maybe it’s a little bit, for many people, too poetic and abstract or something, but when we think about everything being alive and everything being consciousness and we take from this maybe the worldview of Navajos or others that even the wind, even the rocks, everything having its life having its spirit, if people would start to see that and live that way that would really change the way we see the world (and live in the world). It would change the way we relate to everything, if you imagine talking to the wind, listening to the mountain, these kind of direct experiences… what do you feel about that, from your experiences – you’ve heard so many stories and all those songs – what are some of those ones that hit you that might connect to this?

JL Well, one of my dearest friends in this lifetime who has since died was a woman named Rina Swentzell who was a Tewa Indian, a Puebloan woman born into the Santa Clara Pueblo. And we became friends beginning back in the 1980’s and had many, many conversations a few of which I was able to record, but she articulated the sense of the interrelatedness of it all more clearly than anybody I know or ever have known. Although I’ve had it articulated to me by Navajo Indians and Hopi Indians and particularly this man called Camillus Lopez who’s still with us, who is a Tohono Oʼodham, formerly known as Papago Indian. As a matter of fact I included a quote of his for the first part of that book Headed into the Wind, that little frontus line: ‘‘If you look at nature and can’t see yourself in it, then you’re too far away.’’

RK I remember this, yeah this is perfect.

JL And that’s been instilled in me from so many points of view, Native American, Hispano — here in northern New Mexico we have what a lot of people call ‘la raça nueva,’ because the Spaniards came up along the Rio Grande back in 1598 and they settled here and it took some time but the bloodlines between a lot of the different Indian peoples and the Spanish people co-mingled in what they call the mestizaje — the mixture — and so there’s not only a mixture of blood but there’s a mixture of perspective, cultural perspectives — they’re still strongly Catholic but they’re deeply into the land.

Thinking Like a Watershed: Jack Loeffler, Rina Swentzell, Estevan Arellano, and Jack’s daughter Peregrina. Photo by Seth Roffman.

And what I try to write about a lot, and this is one of the biggest concerns I have, in America — this is a bit of an aside — at this moment in time about 82 percent of our population live in urban environments, with only 18 percent out in rural environments — I’m one of the lucky 18 percent in my own estimation, and what that allows me is to really sense it on the deepest possible level, intuitively, emotionally, how interconnected we all are and it is within the rocks and one of Rina’s favorite phrases was ‘O WA HA’ (RK: said with a strong staccato) which means ‘water, wind, breath’ in the Tewa language, and that’s where her mind always was, it’s within the water and the wind. Because that flows through everything. And to me that says it all, says it all to her. I really miss her, I sent that picture to you because those two people in there, Rina and Estevan (Arellano) were two very important people to me because they even though they were from a different cultural perspective they were both brilliant and able to articulate what we were really all trying to articulate together. Now I mentioned that in the note in that book my daughter Peregrina and I did, called Thinking like a Watershed, which is an anthology. But that book, it has several Native American people in it from different tribal cultures. But the upshot is, is that you mentioned to me in that very recent email Nanao Sakaki, who was also a good friend.

RK Really?

JL Yes.

RK Wow. No way.

JL He would stay here with us and I have (laughs) well I have, yeah, right here Nanao – this book (shows Break the Mirror).

RK I have that here too, you know this is one of my all-time favorite books and he’s a big hero of mine. I wish that I could’ve met him, I have to tell you.

JL Well, he was great, and John Brandi by the way knew him extremely well. As a matter of fact he took some of Nanao’s ashes to one of the mountaintops in Tibet and let him go to the wind. Nanao was an amazing person and he was also a very close friend of Gary Synder. Matter of fact as I understand it, according to Gary, Nanao’s personal possessions were stored at the Snyder household when he died so Gary (laughs) had to figure that one out — but the upshot is that one of things that Nanao and I would talk about was the whole notion of how important watershed consciousness really is because he walked everywhere and he looked at watersheds as have I, all of these years.

There’s a … I allude to this in Headed into the Wind I think, I wrote that book about 3 or 4 years ago so you can’t remember which — I mean it’s all a big ‘whatever it is‘, but the upshot is, is that back many years ago when I was working on a project on the Colorado River watershed, my great friend William deBuys, who’s a wonderful writer who lives here in New Mexico, turned me onto a map rendered by John Wesley Powell which shows the watersheds of the arid west.

That’s where the 4 deserts are, and they’re wonderful deserts. The most northerly and maybe the highest is the Great Basin Desert that fills up a lot of Nevada and Utah; and then there’s the Mojave Desert which was my first desert back in the 50s — wow — where I played for atomic bombs being shot off, which was a big moment for me; and then there’s the Sonoran Desert where Gary Nabhan and Camillus Lopez, the Tohono Oʼodham lore master live; and then there’s the Chihuahuan Desert which some people think I live in the northern reaches of, but I don’t think of it that way, I see it as: piñon-juniper-grassland-sort of arid savannah. And according to many people we came into human consciousness in a savannah-like landscape which is: basically you can see a long way. On a clear day from just outside the door of this room where I’m speaking from, I can look out and see a mountain 100 miles to the west, Mt. Taylor, known as Tsoodzil in Navajo which means — it’s the southernmost mountain in the Navajo map of their homeland, Diné-tah.

I’ve recorded Navajos talking about the importance of the mountains, the strategic importance of the mountains to their understanding of their homeland where they feel at home, spiritually, deeply spiritually. And when I lived in a hogan, which is a Navajo — you don’t see many anymore — but a Navajo mud & wood structure, round, shaped like a tipi, it was a male hogan, there’s a photo of it in that book, at Navajo Mountain which is the remotest part of the Navajo reservation — this is nearly 60 years ago now. And that’s when I came to the very clear realization the extent to which habitat shapes cultural consciousness, ‘indigenous mind.’ And subsequently I’ve learned this deeply from the Hopi Indians I’ve spent a lot of time with, the Hopi people and as I say the Tohono Oʼodham people and different other Puebloan people here along the Rio Grande and then in Mexico with — I had a big wonderful time back in 1969 living in a Huichol Indian village and I was documenting their creation myth where they have to walk 500 miles to gather the peyote and then bring it back to their village of San Andreas de Comyata, there’re several other villages… And in October they celebrate this creation myth where they re-enact it while having taken peyote and they offered me peyote to take with them, and I was sorely tempted but those guys walked 500 miles one way (laughing) to get that peyote and I didn’t feel it was a good thing, but at any rate just seeing the beauty of those people and seeing their relationship to habitat — it just blew my mind.

They’re beautiful people, incredible people, and as I understand they were one of the only tribes who resisted Spanish conquest and they moved deep into the mountains, the Sierra Madre Occidental. And I’ve also visited the Tarahumara people there who are amazing people, boy they are the toughest people I’ve ever seen, they run either barefoot or in huaraches up and down the Baranca del Cobre walls, it’s amazing.

RK Did you run with them?

JL I walked. (big laughs) No I, at one point I was — I’d been down there a few times and I was invited to move into a cave for a while with a family, which I did, and I hiked throughout the particular canyon where the Rio Batupilas flows through which is really a deep canyon, and I scrambled up and down that trail a few time. At one point I almost met my fate, ‘cause my friend, Roberto the Tarahumara man, that I was with scampered across this place where an avalanche had crossed the trail and I started to scamper across it and it started to go — the whole avalanche — and I just got into that wonderful state of enlightened consciousness, and danced from stone to stone, and made it just as the stone I was stepping on went over the edge (laughs) — it was really a close call and a very profound moment for me because I realised that what saved me was that other level of consciousness, if it had been just… I would’ve gone over.

RK I’ve had some similar close calls and they’re beautiful to remember (laughs) but the experience…. I was working in the forest doing some conservation work, and we were climbing some very steep and very scree, and mud and dirt … it was all sliding down after a week of summer storms —

JL Oh yeah.

RK — and I leaned against a boulder, it was the size of a small car, like some Japanese car, and the boulder just gave way and went sliding down and —(clap) — hit a tree — wham — knocked a chunk out of this big spruce tree and, you know, I just kind of rescued myself in the moment. There were so many things like that. The mountains can teach you some strong lessons too.

JL Oh, they sure can, so can the deserts.

RK Oh, I wanted to ask you, this is on my list —

JL (laughs)

RK What does the desert teach you? You live there, you’ve experienced so much, maybe this is for a big story but: what have you learned and what does it teach you day-by-day?

JL (thoughtful pause) Well, I’ve lived in 4 deserts now. The first one being the Mojave Desert when I was drafted into the army back in 1957 — that’s when I first came in contact with the desert. I was born in West Virginia and so I wasn’t prepared for this and it was July and it was really hot, way over 100 degrees, and I thought I’m either going to go crazy or I’m going to grow to love it — and within a month I had grown to love it. I just, each evening after the day of whatever we did, we were in an army band, so after that was over I’d go for a walk — walking has been very important to me throughout my entire life — and I’d walk through that desert which was probably the most barren of the North American deserts, and I really got into it.

And then at one point I was hitchhiking from there back to visit my parents, who were then in Cleveland, Ohio, and I passed through New Mexico in what people thought of the northern end of the Chihuahuan Desert, and I knew this was going to have to be my home because it really spoke to me, the beauty of it, it’s just incredibly beautiful. And that was when I first saw NM, and then I worked in the Great Basin Desert in Nevada and parts of Utah, and that to me — the Black Rock Desert, which is part of the Great Basin Desert, at one point back in the 60’s, early 60’s, I travelled the length of that desert. It was on an old two-track road, I had a USGS map that itself was old, I never had any idea if I was gonna get to the other end of the road, and I had two 5-gallon gas cans full of gas plus what I had in the truck, and I got to the next town finally, and the gas tank registered empty. (laughs) But along the way I just was knocked out by this desert and the people I would meet, I met a — and I only met 3 people. I met a buckaroo (which is a sort of an Americanism of the word ‘vaquero’ which means cowboy in Spanish) and this was a retired buckaroo, and he lived out there eating rabbits and, you know, he had a few bucks in his pocket so he could buy beans and whatever. And I met a woman there would was married to a rancher, and then I met an Indian man who was the only one of his tribe left on this reservation. And he invited me to stay there and live with him, and I was sorely tempted to do that but I was working on the project I know I mentioned in the book called ‘America Needs Indians’ with my old friend, Steward Brand, and I had to push on, but — that was a profound moment for me.

And then in the Chihuahuan Desert one of the things that I used to do a lot, I don’t anymore, was run rivers in my raft. I parted with my raft about 10 years ago, there’s got to be so many people on the rivers I knew the rivers didn’t need another one, so I stopped. But I got to run some wild rivers before it was a popular thing to do, and one of them was the lower canyons of the Rio Grande which run between — it’s the national boundary between Mexico and the United States. And…being on a river in deep desert is truly a spiritual experience, I mean, a mile inland from the river on either side and boy, it was drier than a bone.

But I was watching Peregrine falcons and all sorts of beautiful creatures, and truly it’s 110 miles, it took what? 8 or 10 days maybe, and just being out in it, on that level — the desert speaks to me like, probably like no other kind of habitat, ‘cause I really appreciate the aridity. And I realise that the American West, west of the 100th meridian, which runs kind-of right down through the middle of the United States is under siege right now from the elements by virtue of humans having manipulated too much. For example, I just finished an article —a big long essay, for a magazine in Durango, Colorado called The Gulch — I love that magazine. And I wrote a 7500 word essay on the 100th anniversary of the 1922 Colorado River Compact, it turned into what is known as ‘the law of the river,’ and it was a piece of human legislation that did not take in one iota of account of the habitat that surrounds the river. The whole thing was based on presumed human needs as defined by American culture, following a paradigm that had its foundation in economics and also what one man — a man called Sam P. Hayes called, ‘The Gospel of Efficiency’: use every drop of that water. And subsequently ‘the law of the river’ is now being challenged because the amount of water that came down back in those days on an average, of a little over 15-million-acre-feet, has been greatly reduced. And in the meantime while I produced that series in 2001, the human population served by the river was about 25 million, and today, which is 20 years later, is 40 million — and what’s gonna happen?

It’s now pitting agriculture against urban growth, and urban growth to me fosters a perspective that’s totally anthropocentric and to that extent is devoid of any of the peripheral understandings that we have if we engage in indigenous mindedness and see habitat is part of our own mind. So that to me, is such a critical factor and that’s one of the huge lessons that I’ve learned from life in the American deserts over the last 60-some odd years. I will say this, I spent 3 or 4 — from 1958 to 62, mostly in the Bay Area or Big Sur in California before I just needed to be here in New Mexico, and thus remained.

RK I guess I imagine how you said you were on the river you must’ve felt like you were on the lifeline…

JL It is, I mean, it is the lifeline.

RK But to feel it, you must really realize it, I’m thinking about how to put it into words, to share those experiences, it’s maybe not possible, but it would be a big wish for a lot of us, to take people out there and put them in the wilderness and have the direct experience of a mountain or desert or to really be on the river, and then that would — it is to be hoped — would wake up people to realise how important these places really are, and what they really mean. So then when we’re talking about the rights of a river, like is going on now — some rivers have been given rights / citizenship around the world but it still seems to me like — it is connected with indigenous worldviews. For example, the Maori was instrumental in having one of their sacred rivers made into a citizen, so its protected, but it kind of feels connected to what you said I think it was in the RE podcast, and it really spoke to me: that we’re not the stewards of the planet.

JL No, we’re not.

RK That we talk about stewardship and we make these decisions, I believe with good intentions and with a good heart, to think we’re taking care of the planet, and most of the documentaries and campaigns — it’s like: save the planet, protect the planet, give rights to nature… and all those things sound good, but actually it’s still putting us separate from nature —

JL Exactly.

RK — and giving us the power to bestow freedom to the wilderness, or something, and that seems to me completely backwards, and we’re by-passing a very important realization in that.

JL Yeah…. well, one of the things… I’m going to mention two friendships that have really influenced me greatly, one was Edward Abbey and one was Gary Snyder. Ed became my best friend early on, because back in those days we were defending habitat as best we could, the one rule was ‘cause no harm to any fellow human’, and I won’t go into the rest of it. (laughs)

RK (laughs) Well, Jack as just like a side note, in the margin, and maybe it can be part of your answer, but when you mention Ed Abbey I immediately think of: what do you think about monkey-wrenching and when you have this activism, say, nonviolent activism, and then when it’s necessary to get really into it, and when it’s necessary to take it to that next level, or is it ever necessary? Can we do this by peaceful means?

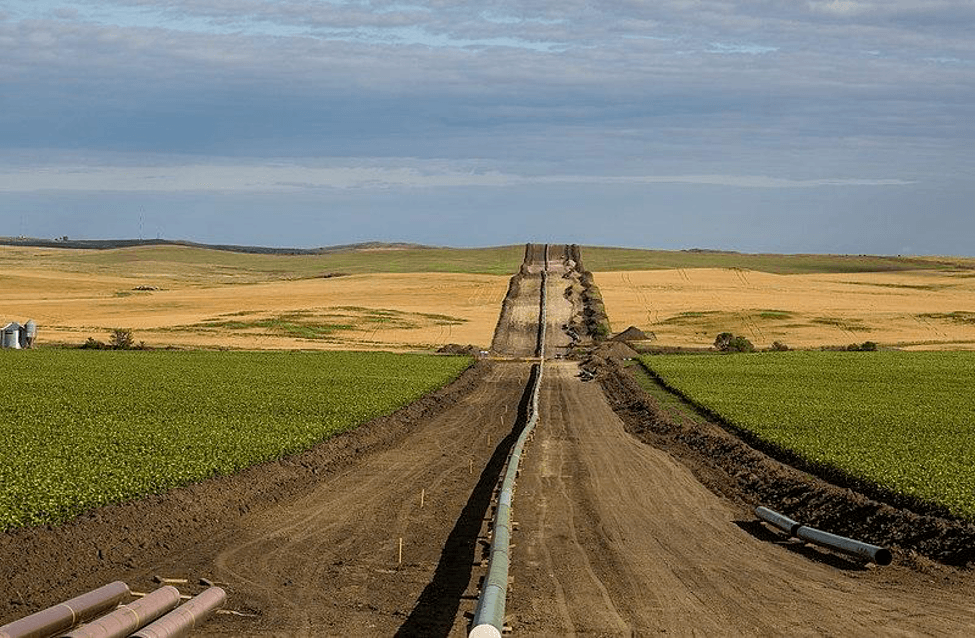

JL Well, this is something. Right now I’m writing an essay called ‘On Direct Action.’ I, up until recently have subscribed to one periodical the New Scientist and I like it a lot, and there was an interview in that magazine with Andreas Malm from Sweden who had written a book called How to Blow up a Pipeline (laughs) which I understand deeply — I mean, literally — a pipeline. And the reason being, back in the Black Mesa days I was made aware of a coal company, The Peabody Coal Company, about to start pumping water out of the aquifer that serves both Hopi villages and Navajo peoples in the surrounding area, to slurry chopped-up coal 273 miles through a pipeline to a power-plant over in southern Nevada. And pumping water at a rate of 2,000 gallons a minute out of that Pleistocene aquifer, just struck me as spiritually — absolutely — the most wrong thing I could imagine. It’s tapping into the heart-beat of the planet, part of the heart-beat of the planet to slurry coal to light up Las Vegas, Nevada. And I travelled pretty much the length of that pipeline, either hiking or however, and I thought about it — and I didn’t. But I understood his thinking. I later talked to somebody who’d been one of the designers of that pipeline, and if I’d have done it, that would’ve shut the whole thing down for all time ‘cause they couldn’t do it again. (laughs) And I thought ‘gee whizz.’ (big laugh) But I also thought ‘what happens if the power goes off in a hospital and somebody’s on an operating table and they die because of that’, and I just couldn’t do it, and this became a huge subject with Ed and me. Ed and I got to know each other very, very, very well. We hiked thousands of miles together, we ran rivers together, we camped hundreds of nights throughout the American southwest together, and we talked, and talked and talked and talked!

About Jack Loeffler:

Jack Loeffler is an aural historian, environmentalist, writer, radio producer, and sound-collage artist. His Navajo friend, Shonto Begay writes, “by documenting the voices and stories of the land Jack moves us and helps us to rediscover our own voices.” Jack’s daughter says, “He makes friends everywhere he goes, because he cares. He empathizes and connects with every living being he encounters. From the child sitting across from him at a restaurant to the Navajo elder, and the great horned owl to the spiny cholla cactus, he cares about it all.” He was a founder of the Black Mesa Defence Fund.

By Jack Loeffler:

Headed Into the Wind: A Memoir; Survival Along the Continental Divide: An Anthology of Interviews; Voices of Counterculture in the Southwest; Adventures with Ed; La música de los viejitos: Hispano Folk Music of the Río Grande del Norte; Healing the West: Voices of Culture and Habitat; Headed Upstream, Interviews With Iconoclasts; Thinking Like a Watershed: Voices from the West; & a lot of radio shows (about 400). He has recorded 3-4,000 folk songs and his recordings of indigenous peoples, songs, stories, and interviews with many activists, musicians, and the places themselves as soundscapes are now available from the Smithsonian and at the Museum of New Mexico.

Rowan Kilduff is a dad, mountain-runner, and activist-artist. He writes on the connection between ecological and world peace; wilderness, urban wildlife, and forests, and he is the author of a few books, as well as various articles that appear in print and online. He lives in Central Europe, currently up and down between 49 and 52°N.