Defending the East’s Last Big Cat Population

Featured Image: Connie Bransilver, US Fish & Wildlife Service. Public domain

By Jaclyn Lopez, Center for Biological Diversity

The Center for Biological Diversity uses science, law, policy and the media to help reverse the trend of species decline and extinction in Florida and recover the state’s most at-risk animals and plants. We fight against extractive industries that threaten the region’s most imperiled wildlife, advocate for species threatened by climate change and sea-level rise, and work to protect Florida’s productive freshwater, inland, and coastal ecosystems.

Florida is home to an abundance of plants and animals found nowhere else on Earth. With an estimated 700 vertebrate species, more than 30,000 invertebrate species and 2,840 native plant species – the largest assortment of plant families in the United States – Florida is an international hotspot of biodiversity. Of these many species, a total of 147 vertebrates, 410 invertebrates and 295 plants are unique to the Sunshine State. Sadly, Florida is also home to the second-highest number of endangered species in the contiguous United States.

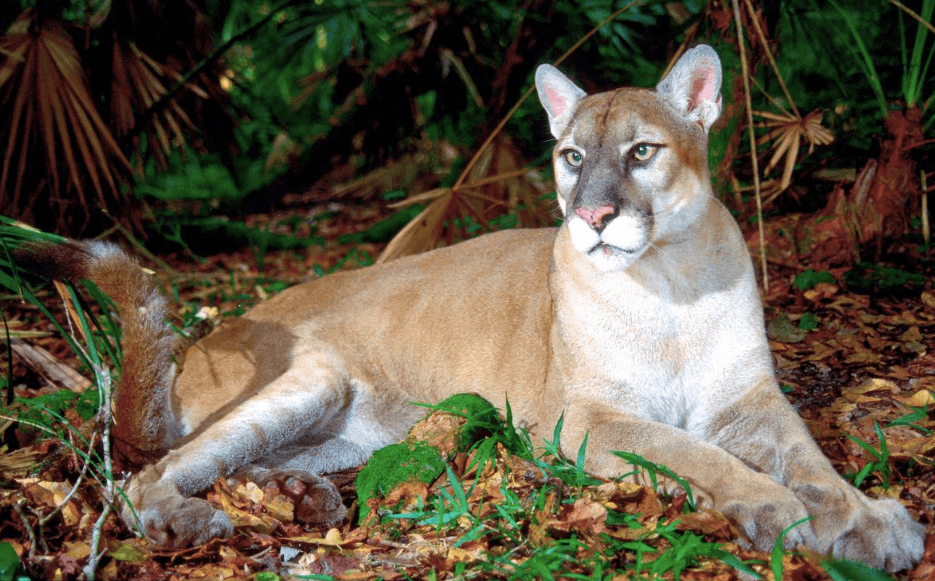

Among the most beloved, is the Florida panther. Panthers are shy, powerful predators few Floridians have had the opportunity to see in the wild. Habitat loss – fragmentation and degradation – is by far the greatest threat to the panther. Panthers once ranged widely across the southeastern United States, but are now reduced to just 5% of their original range.

Because of this principal threat, in 2009, the Center and partners petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to designate 3 million acres of critical habitat for the panther. The panther was listed as an endangered species back in March 11, 1967, before Congress amended the Endangered Species Act requiring that FWS concurrently designate critical habitat. Nonetheless, Puma concolor coryi persists on a final stretch of relatively wild land in southwest Florida, in the Big Cypress/Everglades physiographic region, on approximately 3,500 square miles, south of the Caloosahatchee River in Collier, Lee, Hendry, Miami-Dade and Monroe counties. While panthers can roam beyond this space, having been found north of the Caloosahatchee River in Flagler, Highlands, Hillsborough, Indian River, Okeechobee, Orange, Osceola, Polk, Manatee, Sarasota and Volusia counties, panthers, especially females, generally do not cross the Caloosahatchee River (which has been channelized and in places is fronted by extensive development).

It is in this relatively small corner of the world that the East Coast’s last big cat must carry out all of its basic life functions, like breeding and feeding. Male panthers are polygynous and need large home ranges with several females. Young panthers will stay with their mothers for over a year before leaving to seek to establish their own home range and mate. Generally, daughters choose territories near their mothers’, whereas sons disperse widely. A panther’s life is largely solitary – juvenile males need to an average of 25 square miles of home range, with secondary dispersal habitat of an additional 145 square miles…for a single panther. Therefore, dispersal is key to reproduction, population growth and the overall survival of the species. When there is not enough habitat, cats may turn on each other – this “intraspecific aggression” accounts for a significant amount of all discovered panther mortality annually, second only to collisions with vehicles.

Panthers need their extensive habitat to have sufficient prey. They feed primarily on white-tailed deer and feral hogs, but will eat other prey including raccoons, armadillos, marsh rabbits, and alligators. Deer density is greatest in hammocks, pine forests and marshes, but these are also the areas most impacted by habitat loss.

Panther habitat in Florida today also needs special management and protection. For example, with natural wildfire regimes disrupted by development and fire suppression, periodic prescribed fires are necessary and improve habitat for deer and hogs. Some areas need to be regulated to limit use of off-road vehicles. But the most significant impact to panther habitat is the conversion of natural landscapes to residential development in southwest Florida and all of the roads and traffic that creates. Constructing new and upgrading existing highways, expensive wildlife underpasses notwithstanding, increases traffic volume and impedes panther movements between habitats. These same highways can, in turn, stimulate further residential and commercial development.

Between intraspecific aggression and collisions with vehicles, both attributable to habitat fragmentation and destruction, habitat loss is the primary cause of the panther’s endangered status. Yet, FWS refused to act on the critical habitat petition, and we were unsuccessful in the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals in compelling FWS to designate critical habitat. To this day, the Florida panther does not have designated critical habitat, but the Center for Biological Diversity and partner groups continue to work for it.

Florida Panther (Credit: Larry Richardson, US Fish & Wildlife Service. Public domain.)

In 2011, the Center and partners petitioned FWS to reintroduce panthers to the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. In addition to protecting the last remaining Florida panther population’s southwest Florida habitat, areas for panther expansion must be identified and panthers reintroduced. The 2008 Florida panther recovery plan calls for establishing two additional panther populations to help reduce the risk of extinction. The recovery plan explicitly identifies the Greater Okefenokee ecosystem of southern Georgia and northern Florida. In fact, two live experiments confirmed that the area would support panther reintroduction. But, again, FWS rejected our petition and to date has failed to follow the recommendations of its recovery plan and reintroduce panthers anywhere.

In 2013, the Center and partners launched a lawsuit challenging federal permits authorizing a sand and limestone mine in core panther habitat. Not only was the mine site on panther habitat, at least 31 panthers had been documented within a 25 mile radius of the mine. Additionally, seven documented Florida panther traffic mortalities had occurred within five miles of the project site, and the mine was projected to significantly increase truck traffic. Another troubling aspect of the project was that the mine was identified as the future site of a new town. In other words, once the limestone and sand had been removed from the mine, the large holes left behind would become featured “lakes” for future residential development. Such development would further worsen traffic. Unfortunately, we were unsuccessful in getting the permits rescinded, but to-date, the mine has not been built.

Also in 2013, the Center and partners filed a lawsuit in an effort to reduce off-road vehicle use in Big Cypress National Preserve. The lawsuit against the National Park Service alleged that it violated the Endangered Species Act and the Park Service’s own Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan by designating hundreds of miles of new trails for off-road vehicle use in the preserve. The preserve provides the largest intact habitat for the panther; and the roads threatened to damage the fragile ecology. We were ultimately successful in reversing the Park Service’s decision to open up those areas to additional off-road vehicle use.

In 2014, the Center and partners convened the Florida Panther Symposium to discuss conservation measures to recover the panther. The symposium convened key stakeholders and about a hundred members of the public and addressed preserving the functionality and spatial extent of existing habitat, while identifying opportunities for initiating reintroduction of panthers farther north. While a lot of valuable information was shared and there was clearly interest in reintroduction, there’s been no indication that FWS intends to reintroduce panthers anytime soon.

In 2016, the Center and partners filed another lawsuit against the National Park Service, but this time for authorizing extensive seismic exploration for oil and gas in the Preserve. The Park Service authorized a Texas oil company to explore more than 110 square miles (70,000 acres) of the swampy preserve using enormous vibroseis trucks through roadless areas of the preserve. We were unsuccessful in overturning the Park Service’s permits and the seismic exploration did in fact flatten everything in its path, levying miles of damage to the preserve, some of which may never be restored – including forests of hundred-year-old dwarf cypress. We have been monitoring and documenting the destruction and are hopeful that with the information we’ve assembled, the Park Service will be less eager to authorize future seismic exploration activities in the preserve.

There are a number of other habitat-destroying projects that threaten the panther, including a new gas-fired electrical power plant, a 4,000-acre residential-commercial development, a 2,960-acre residential development, a 1,300-acre development, an 18,000-acre development with 20,000 new homes, several other relatively small developments (550-1,837 acres) and mines, and dozens of road-widening projects. But the largest planned habitat impact is a proposal by a dozen landowners in southwest Florida to develop 45,000 acres with a projected additional 182,960 vehicles in eastern Collier County, increasing daily trips on the deadliest road for panthers by 300-400%. This is despite the fact that a leading panther scientist found that all remaining breeding habitat in south Florida should be maintained and expanded, and that FWS has already authorized development in at least 144,817 acres of panther habitat since 2000. If approved, this proposal would push the panther over the brink, and bring near-certain extinction for the last population of our greatest cat in the East.

What you can do: Please support the Center for Biological Diversity, Conservancy of Southwest Florida, South Florida Wildlands Association, and other groups working to protect panther habitat and urge the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to protect their last remaining habitat in southwest Florida and restore panthers to additional wildlands in their historic habitat, including Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. Call on Congress to block attacks on the Endangered Species Act, and to protect wild places like Okefenokee. Finally, this November, vote for candidates committed to preserving rather than dismantling our nation’s bedrock environmental laws.

______________________

To read the research article, click Landscape Analysis of Adult Florida Panther Habitat_2015_Frakes et al

Jaclyn Lopez, Florida Director, Senior Attorney, is a Florida native and has been with the Center for Biological Diversity since 2002. She holds a master of laws degree in environmental and land-use law from the University of Florida, a J.D. from the University of Denver Sturm College of Law and a master’s degree in urban planning from the University of Arizona. Jacki coordinates campaigns in the Southeast and Caribbean, focusing on protecting imperiled species and ecosystems. She has presented and written on numerous Endangered Species Act issues and taught courses on environmental law. Contact: 727.490.9190, email Jaclyn Lopez.