One Ocean…One Song…One Ripple….

Fifth essay in the United Divide© series by Michael D’Amico

Featured Illustration by Pinky Twolegs

In March 2019 the United Nations declared 2021 to 2030 to be the Decade of Ecosystem Restoration, with the objective of restoring degraded ecosystems as a measure to fight the climate crisis while enhancing water supply, food security, and biodiversity. These issues were daily news headlines until eight months later when a swift moving virus jumped species and circled the globe, knocking the earlier issues to the back pages, but not stopping them from happening. Severe weather and habitat destruction keep on rolling on. There is still time to reverse the climate and extinction crises, but it is widely acknowledged we’ve only about ten years to pull this off before reaching the tipping point of no return.

How do we get out of this morass we humans have created? Well, since all indications are the global industrial explosion has brought us to the brink, it stands to reason that only an implosion of this global industrial system, such as we witnessed in the spring of 2020, can pull us back. The UN’s declaration offers us that template.

This UN call for ecosystem restoration compliments the Nature Needs Half call for protecting and rewilding fifty percent of the Earth by 2030. So, we’re told we’ve ten years to stem climate chaos, but taking into account robust populations of apex predators like some species of sharks, we also need to think and act in terms of a hundred years. This is doable, but it will require everyone everywhere to do their bit to restore the natural flow all life depends on.

Given that ecosystems are networks of interconnected systems, so perhaps should be our approach to rewilding them. Many positive life-saving actions are taking place, but for the most part they are fragmented. The challenge is finding ways to tie all of these pieces together.

Before getting to the centerpiece of this puzzle of restoring ecosystems let’s first give attention to the human behavior changes needed to afford equal rights and respect for all species:

*voluntarily—and without suffering—reduce our numbers so that overpopulation no longer drives destruction;

*stop over-consuming, especially those of us in affluent nations;

*begin practicing conservation as if on a war-time footing but in a peaceful manner;

*transition to locally based economies for our primary source of needed goods while maintaining a good quality of life and gradually relegating the global economy to a secondary role—with an eventual phase out;

*end our aggression towards each other by all agreeing this is not an us or them undertaking but rather it’s a we—as in the global community we, so as to gain the advantage of feeling connected while taking away a major tool the manipulators and spirit killers use to keep us separated into rural versus urban or individual versus group or old versus young or the able against disabled and so forth;

*treat healing the world as an egalitarian undertaking and let leaders emerge from the ranks;

*stop acting like humans are the center of the universe and separate from the natural world, and begin recognizing we’re but one component of nature;

*last but not least, slow down our daily activities and begin dialing it all back—way back—because what good does a pocket full of money and a mind full of stress do for you if you can’t breathe the air, drink the water or feed your family?

This is all easy to say while hard to accomplish, of course; but there are ways to compliment all ongoing efforts for the greater good that, whether done individually or collectively, aid in rewilding degraded ecosystems.

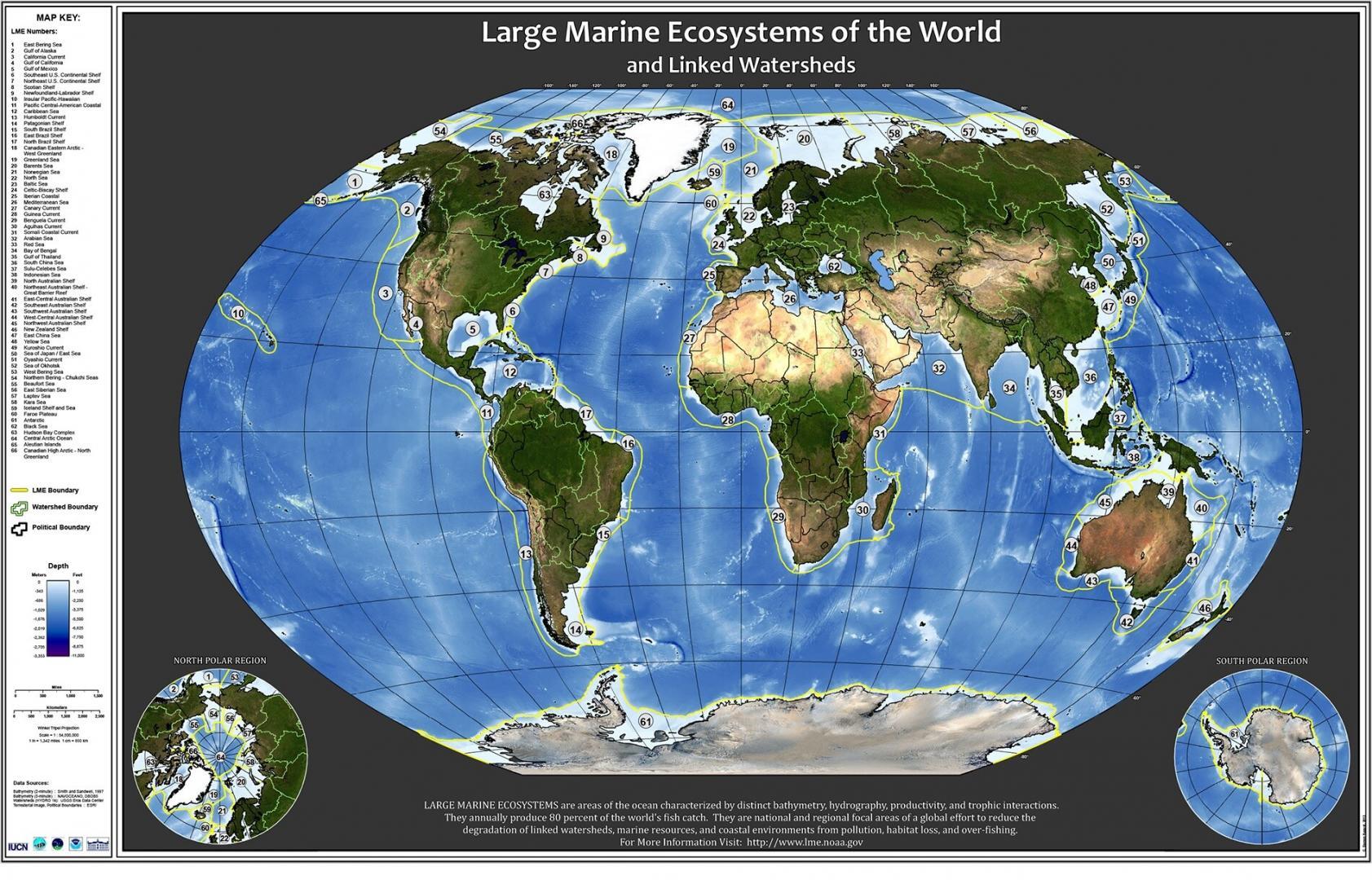

For this rewilding essay’s objective we’ll come in from the high seas and head up into every accessible headwater. Food security and water will serve as the commons and the ocean as the ecosystem to restore. Here, to illustrate one way of doing it, we will cover three of the five oceanic basins covering approximately half of the world’s large marine ecosystems and encompassing well over a hundred countries. For the initiated with works-in-progress, if you see any aspects of this essay that fit into your goals, please incorporate them. For the uninitiated, if some aspect of this triggers your imagination and propels you to take action, feel free to wade in; the water’s fabulous—just don’t forget to keep an eye out for Bull Sharks.

The three oceanic basins this essay will focus on are the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific wherein each one lie multiple large marine ecosystems. Each LME is a composite of river basins and estuaries and oceanic waters that serve as the nexus between the high seas and the headwaters. The ecosystem ambassadors for our purposes here will be five of the sixteen species of Anguillas, common eels, listed under the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Anguillid Eel Specialist Group. If these eels don’t do it for you, or they do not occur where you are, choose an ambassador that does, like Pacific salmon or Red Knot shorebirds or a grand boulder migrating down to a pebble.

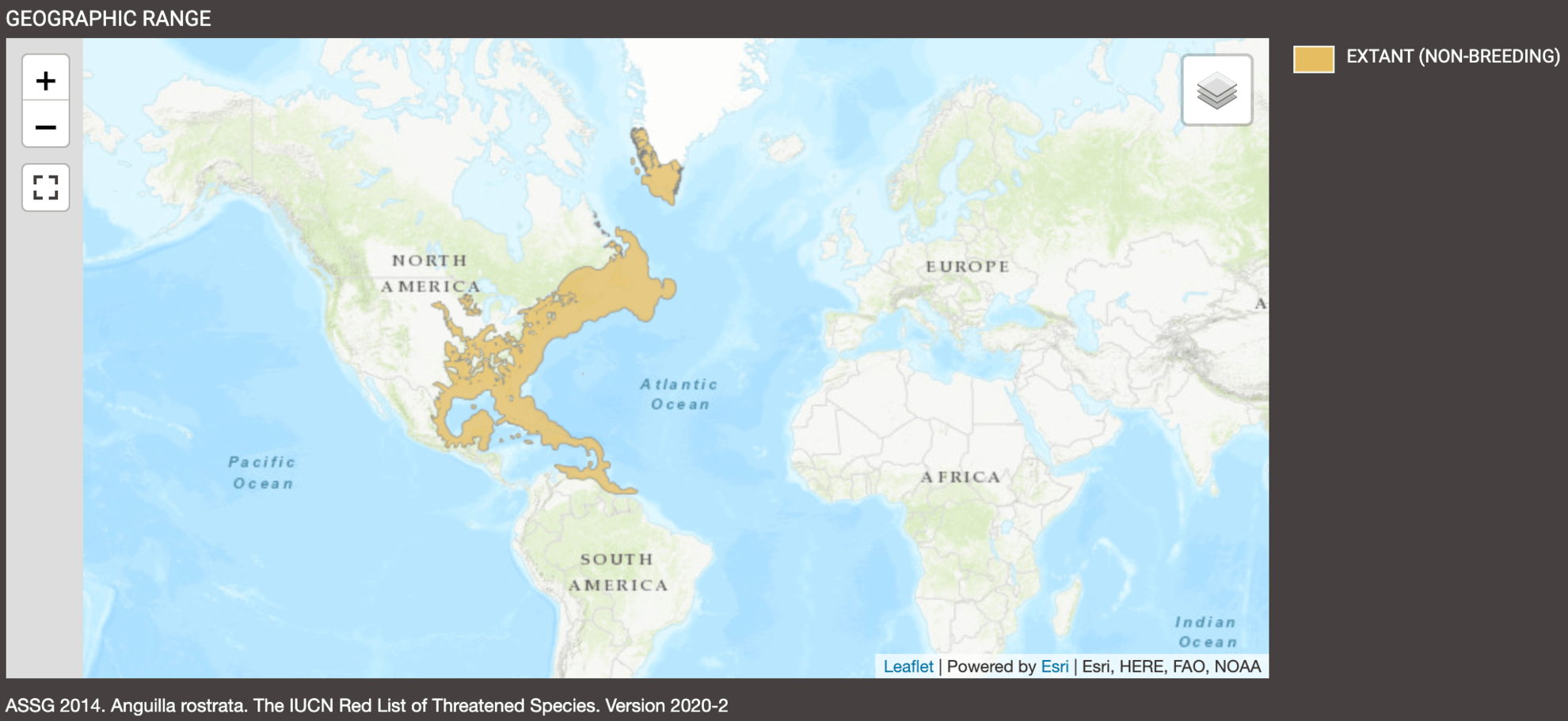

The five Anguillas are Anguilla japonica (Japanese Eel), A. australias (Australian Eel), and A. bicolor (Bicolor Eel) found in the Indian and Pacific basins and A. rostrata (American Eel) and A. anguilla (European Eel) in the Atlantic basin. We’re going to ripple in with them from the high seas to your home waters. This can be seen by marking where you are on the Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) map and overlaying it with your local Anguilla geographic habitat range from the IUDN Red List Anguillid. I suggest you bookmark your IUCN Anguilla page for referencing later on such matters as threats, conservation actions in place, and actions and research needed. Now that we have the blueprints and the tools in the toolbox, we can get to work.

Work?!!! Fear not, it’s good work, honest work, where there is something for the experienced and inexperienced alike and if climate or biodiversity doesn’t do it for you, think breathable air, drinkable water, and food security. If we do this right there should be plenty of wild flesh, grains, fruits, herbs, nuts, and vegetables to go around. Free food. Real food. Food security for all, no matter if one’s a carnivore or omnivore or vegetarian or vegan; be one finned, feathered, furred, or foliaged. We’ll all meet down by the water, agree to disagree and remain civil about it, as we get to work rewilding these habitats.

Anguillas have been chosen as our ecosystem ambassadors partially because of their epic journey from birth to death. They are diadromous and found in many waterways of the world’s temperate and tropical regions, bridging divergent aquatic habitats. They are born in the high seas and migrate into continental waters where they live among us, sharing our neighborhoods, until they return to the sea where—we believe but do not know for certain—they spawn and die.

To highlight this we will look at American Eels primarily and European Eels secondarily in the Atlantic basin. They are considered a panmictic species who begin their short-lived egg stage in the Sargasso Sea before hatching into larval leptocephali. In this phase they appear willow-leaf shaped and flat from side to side. While still in this oceanic environment they’ll morph into the glass eel stage where they take on the adult-like cylindrical shape before making their way into salt bays, brackish estuarine, and freshwater habitats. This can take the little eels a year or more before getting settled into their new home and begin adopting pigmentation leading to the elver, yellow, and silver stages. For the next 3 to 30 plus years this chosen place will be their residence where they will not venture very far until eventually a day comes when a rhythm known only to them kicks in and the silvers who are ready will begin their migration back to the ocean. As the seasons turn the annual cycle begins again (as Rachel Carson described beautifully in her first book Under the Sea-Wind).

Iceland appears to be the separation point. European Eels move down the eastern edge of the Atlantic basin and occupy every accessible freshwater, estuarine, and marine habitat from Scandinavia to North Africa. American Eels will come down the western edge and do the same from Greenland to Venezuela.

Natural predation takes place all along this circular journey, where eel feed on insects, fish, fish eggs, crabs, worms, and such. Conversely, they are the prey of many species of birds, fish, and mammals.

We humans have a long history with eels, with all the markings of them being one of our survival foods over the ages. This long history is exemplified by the 6,600 year old weirs made of volcanic rocks in Australia known as the Budj Bim Indigenous eel trap site which in 2019 was added to the UNESCO World Heritage list; by the ancient Egyptians seeing Anguillas as a minor god; by Aristotle and later on Pliny the Elder pondering Anguilla’s lifecycle; by Sigmund Freud trying to find the gonads of male eels for his masters thesis; by the Danish researcher Johannes Schmidt putting to sea in 1903 to find the spawning grounds of the Atlantic basin’s common eels and staying at it for eighteen years, interrupted only by World War I, and finally sharing his findings in a report to the Smithsonian Institution in 1924; by Rachel Carson beginning her dissertation at John Hopkins University in 1932 on how the eels adapt to different water salinities throughout their lives (before extenuating circumstances pulled her away); and by the Algonquin people of Ontario who in 2012 issued a declaration on how for them the eels are sacred and are the prayer carriers as well as an important source of food, medicine, and ceremonial uses.

Today we know the numbers of American, European, and Japanese Eels are in steep declines. Throughout their high seas ranges to the headwaters and back, Anguillas face many adversities such as changing ocean currents/climate chaos; urban and industrial developments; drought; disease; over-fishing; pollution; habitat loss/barriers to migratory pathways; and over-consumption by humans.

Every segment of these migratory corridors must be protected and rewilded where necessary, starting with the nursery grounds. Local voices from around the world can help by advocating for their governments to declare the whole internationally shared ocean environment of the Sargasso Sea a Marine Protected Area and to allocate funds for strong enforcement. All commercial and industrial-scale operations such as factory fishing, undersea mining, shipping, and sargassum seaweed extraction should immediately cease. Same goes for any other Anguilla nursery grounds when they come to light, such as happened recently as we learned the Japanese Eel larvae emerge west of the Mariana Ridge near Guam. If you take both the ecological and food security standpoints, you’ll be lobbying on solid ground.

The same message applies after the eels enter into a governmental jurisdiction, whereupon the direct pressure needs to be applied primarily by that nation’s citizenry and secondarily by others outside of it whose eels migrate into that area. All commercial and industrial-scale activities should be banned such as fishing, mining, coastal armoring, channeling, dredging, and energy development.

Within each watershed we need to unshackle our rivers starting with human-made dams and water diversion systems. On the local level, one can start with those deadbeat dams built ages ago that now just sit there and block the natural flow. The big dams will take more time and planning. Best to do it now before nature does it for us, and avoid as much as possible any further damage to the riverine system. Time to let the fish go up and come back down with the sediments. In Europe a smartphone application known as AMBER Barrier Tracker has been developed that allows citizens to identify riverine obstacles to migratory fish with the intent to get these waterways re-connected. Be nice to see this concept expanded to the global level, with every watershed color-coded to show existing (Red), removed (Green), and proposed structures (Yellow). This latter point is especially important where dam opponents are being assassinated and whole communities being wiped out.

To date, most of our information about how eels are faring is on the American, European, and Japanese Eel populations and is mainly based on the collection of economic data over the years. The data point to another critical local-to-global component of rewilding. This is the banning of the unbridled hunting of the glass/elvers, yellow, and silver Anguillas by humans, if one wants to protect and restore their local ecology. Eels are now hunted in every life stage except the eggs and larvae, and it’s even possible some humans are now going after those beginning-life stages as well because Anguillas are big business. In 2004, the commercial eel trade was estimated to be $2 billion globally. Much of this still happens as backwater cash transactions and is hard to monitor. Human over-consumption is the culprit.

The first thing to shut down is the capturing of wild glass eels and elvers, who are shipped off to be enslaved in industrial-scale confined animal feeding operations because they will not breed in captivity. Whoever figures out how to get them breeding in captivity by creating the Frankeneel stands to make a lot of money. Many of these big CAFOs are found in Asia and Europe, but the USA is also seeing more and more of these types of operations.

Local-sized operations to feed the local community are one thing, but these large Anguilla CAFOs are another, since they wreck not only direct havoc but global as well. One illustration of this global point happened when the European Union shut down hunting of the endangered European glass and elver eels, whereupon pressures quickly switched from the EU region to the wild baby Anguillas being taken from North Africa, the western Atlantic basin, and the Philippines. Like most wildlife crimes, poaching of baby eels goes on under the radar. Local watchdogs taking local action to protect and restore their watershed’s eels and habitat by every peaceful means necessary will go a long way to stemming this international trade. There is no one size fits all, so get creative. At the backend, consumers need to stop purchasing those eels raised in industrial-scale CAFOs. This ties up the economics at both ends; and if one needs an incentive beyond ecology, they can think of it as protecting a local source of wild food and medicine. If you’re going to eat eel flesh, eat locally wild-caught only.

At the other end of this fishery spectrum is the commercial catch and exportation of silver eels. We must allow the wild adults to get back to the high seas without any hindrance. Some ethical fishing cooperatives take this into account and accordingly allow a large percentage of them to pass back out to sea.

The major component missing across the planet is a constituency for eels. The IUCN WAG tracks the global Anguilla picture and the niches that need to be filled, which can be found on the aforementioned link to your local Anguillas; so wherever you are, you can help out there. On the multi-national level the European Union has a European Eel plan in place that is ever-evolving, but the EU is a unique system and what works there probably won’t work in other places, so different approaches are warranted. The USA is poised with the tools on hand to offer an alternative way of demonstrating global cooperation for full ecosystem restoration. Here’s one possible approach to get that started by just using the lifecycle of American Eels and the Large Marine Ecosystems.

From the mid-1980s to 2000 the USA Department of Commerce’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) created the Estuarine Living Marine Resources to index the distribution and abundance of fishes and invertebrates. The criteria for these ELMRs will serve here as our template focusing on the American eel and expanding out of the estuaries to take in their historic to present geographic range and including habitat assessments. For the most part, these are public lands and waters. This means taking into account the subaqueous lands and waters of every watershed from the headwaters out to the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone 200 nautical mile territorial sea baseline marker. Such a conservation initiative can serve to become an international cooperative since American Eels migrate to waters controlled by governments from Greenland to Venezuela, to the Caribbean and the First Nations. The only waters traversed by eels but not covered here because they are not governed by a single entity are the oceanic, yet if we came together and spoke in one voice they would be.

In order to heal the waters we’ll need to heal the riparian buffers along the streams up to each side of the watershed’s divides. In the USA we say that if your waters are swimmable, fishable, and drinkable you’re doing okay, but this proposal goes way beyond that in terms of thinking food, shelter, and freedom of movement for all species. Here again Anguillas show us the way. Back in the days when the rivers ran free, eels were very abundant in the waters of the East Coast and are said to have comprised 25 percent of the total fish biomass in the streams; but as of the year 1998 it was estimated that diadromous fish species might be hindered from as much as 84% of their historic range in the Atlantic coastal watersheds. That’s a lot of destruction of riverine public lands; and that statistic does not take into account the full loss of historic habitat range of Anguillas–which includes the drainages emptying into the Gulf of Mexico.

Where the ripple greets the land, here we start rewilding the riparian areas and don’t stop until we get up to the watershed divide. Along these streamside corridors and beyond, we’ll need to remove the exotics and replant native trees and understory flora. These are the starting points of watershed and eel recovery. It’s not hard to keep going if the mindset and actions are projected seven generations ahead.

If the land or sea doesn’t do it for you, pick your favorite bat, bird, butterfly, or bug that shares your neighborhood during some part of his or her lifecycle as your ecosystem ambassador. By combining the rewilding of the air, land, and sea habitats one invites in the pollinators and restores predator-prey relationships that ultimately lead to a better quality of life for all.

Granted this is merely a vision, but one that we know from places like Yellowstone National Park can play out with the return of the wolves. That landscape is a lot healthier since the return of this apex predator. So with that in mind here’s another possible scenario.

Imagine for a moment a great public-private cooperative initiative to assess the ecology and economics of viable wild fish habitat that leads to the ecological restoration of your LME, done on the local level. By using the ELMRs as the template and overlaying them with both the political boundary markers and the migratory routes of the fish, in this case the common eels, we would then have a much better handle on what needs to be done. Such an assessment would not only involve nearly every branch of the federal government but also state, county, and town governments, along with the private sectors that employ thousands of people.

How does this cooperation happen? Well, start by not becoming complacent in thinking any day now things will go back to normal, as in global industrial normal. In terms of thinking recent past, present, and future foreseeable, we can see we’re a heartbeat away from scrambling for food and water. Many of us have lost our traditional knowledge, in that there is cheap food all around us. Fortunately, much of this knowledge still exists, and we should be embracing and applying it to reestablish food forests and wildlife migratory corridors.

As most experienced Mother’s helpers will attest all great actions begin with simple steps. Witness a lone teenager protesting in the cold outside the Swedish Parliament joined by another braving the chilly winds coming off the East Strait at the UN Headquarters together inspiring millions of like-minded people around the world taking the protest to the streets.

You can start your reattachment to your landscape by rewilding your yard with native vegetation and get a wild Three Sisters garden going and let those leaf blowers and lawnmowers sit idle. Start indoor herb and vegetable container gardens for the winter months. Feeling hemmed in due to the pandemic with the kids or missing the company of your family and friends? Why not go ground-truth the land with them from your home to your nearest surface waters following the same pathway the drops of water take. From an educational standpoint, it’s a good learning tool to show how all those lawn chemicals and insecticides get into the water as non-point source pollution. Do it rain or shine. Along the way wildlife will appear, as will point and non-point pollution sources reminding you to properly dispose of your chemicals from home or better yet stop buying them. For young people filled to gills with anxiety, why not instead fill your quills with nontoxic native seedballs and walk, bike, or skateboard and start tossing them onto those degraded landscapes away from busy highways and let the elements take it from there. Enjoy. Maybe you’ll get lucky one day and observe a Great White Heron with a yellow eel wrapped around her beak in a life or death struggle, or at dusk see a mass of eels migrating across a rain-soaked field to get around a riverine barrier.

Can’t get out for some reason? Confined to home? No problem. Research is needed. Help build a local water quality and wildlife database. Monitor public notices and comment on issues affecting your watershed. Send a hand-written letter to a politician or submit a letter-to-the-editor of your local newspaper. Monitor governmental appropriations and match them up with the funding agreements, particularly the federal to the state. Are they doing what they said they’d do, and are these actions enhancing or degrading your watershed? If the latter, hold them accountable. Research who owns those dams and start organizing to get them taken down and to oppose any new ones. The common denominator for those who can get outside and the homebound alike is the shared purpose of healing your watershed. Nature is resilient and will rebound if given the chance. One of the advantages many have today that we never had before in our history is to be able to communicate with each other almost instantly no matter where we are. Using these tools judicially—and remembering to turn them off or unplug them when the tasks at hand are done—will go a long way.

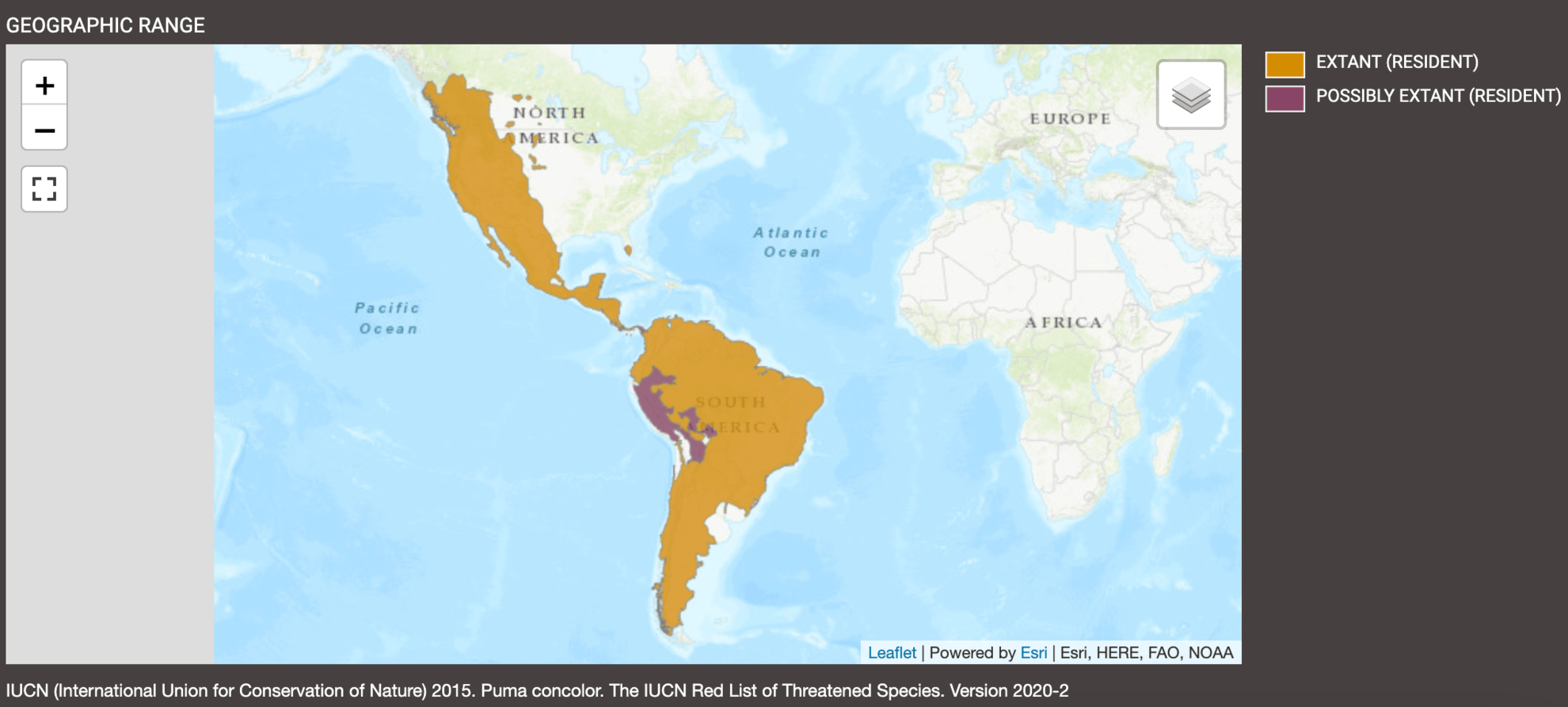

Again with the successful reintroduction of Wolves to Yellowstone National Park as the template, let’s look at the continental USA from east of the Rockies divide on down to the Gulf Coast and over to the Atlantic seaboard. To see how rewilding on such a scale could work, overlay the current IUCN Red List habitat maps for American Eel and Puma, remembering that these two keystone species once occupied most of these lands and waters from the Canadian Maritimes through the Gulf of Mexico.

American Eel IUCN habitat range map (Source: ICUN)

Puma IUCN habitat range map (Source: IUCN)

What’s revealed are the remaining accessible locations for the eels in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico drainages and, with the exceptions of a handful of isolated locations in the mid-West and southern Florida, the near nonexistence of Pumas east of the Rockies. Imagine now those riparian habitats being rewilded, and along with the eels and healthy stream-side forests would come Beavers, who serve as another prey item—along with Pumas’ preferred quarry, the White-tail Deer, which are now abundant in much of the East—for the Pumas as they expand east of the Rockies and back into their historic range. Riparian restoration can translate into Puma corridors all the way to the coast, but habitat restoration alone won’t do it. This action must be coupled with an enormous lobbying effort by folks teaming up to reform state fish and wildlife agencies combined with those working to establish safe wildlife road crossings and with those roaming the halls of the capitals the administering of appropriations and so forth. By connecting those and other similar efforts, while holding the purse strings of transportation and fish and wildlife agencies, we can bring about change.

Below is a collection of suggested readings, audios and visuals, should you wish to venture further than this essay can take you. They do not include my personal experiences related to the subjects at hand. Best save those tales for another time. Some items in this list are directly related to Anguillas and some are not. Taken cumulatively they are all interconnected, but they do not have all the answers, like how do baby eels know when they’ve arrived at that freshwater stream or pond that this will be their home for many years to come before returning to the sea. Perhaps we’ll never know, and that ain’t all bad.

Suggested resources list:

Under the Sea-Wind, First published by Simon and Schuster 1941, Rachel Carson © 1941

consider the eel a natural and gastronomic delight, Da Capo Press 2004, Richard Schweid © 2002

“Returning Kichisippi Pimisi, the American Eel, to the Ottawa River Basin,” Algonquins of Ontario © 2012

In the Shadow of the Sabertooth, CounterPunch and AK Press 2013, Doug Peacock © 2013

Anguillid eel conservation: A global perspective, UBC Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, January 21, 2019, YouTube, https://youtu.be/hpYyFetCvIM

Fishbase 2016: Willem Dekker, Fishbase Sweden, December 13, 2016, YouTube, https://youtu.be/0-6dtXSUuuo

Eel Traditions, UINRTV, April 5, 2013, YouTube, https://youtu.be/-SvDxwilv9A

AMBER Barrier Tracker, Amber Tools, April 12, 2018, YouTube, https://youtu.be/QjHJwy2wODM

Why Our Lifestyles Need To Change – Dr. Jane Goodall on London Real, September 8, 2016, on YouTube, https://youtu.be/B2W7PvBu5sw

Unbroken Ground-A New Old Way to Grow Food, Patagonia, August 4, 2016, YouTube, https://youtu.be/3Ezkp7Cteys

A guerilla gardener in South Central LA – Ron Finley, TED Talks, March 6, 2013, YouTube, https://youtu.be/EzZzZ_qpZ4w

All Rewilding Earth podcasts. Suggested starters in relation to this essay are: