The Jornada Hawk: A Brief Case Study in Decolonizing Nomenclature

Mexican poppies in their saturation-slider hues of orange and gold and yellow surround my family and I as we soak in the warm March sun and behold the splendor of Castner Range National Monument. It’s the first day of Poppies Fest 2024, an annual tradition in El Paso, Texas, that celebrates the vernal arrival and accompanying pops of wildflower radiance amidst the Chihuahuan Desert mixed grassland and shrubland. These abundant biological indicators harken a happy season as the one-year anniversary of national monument designation arrives on the near horizon.

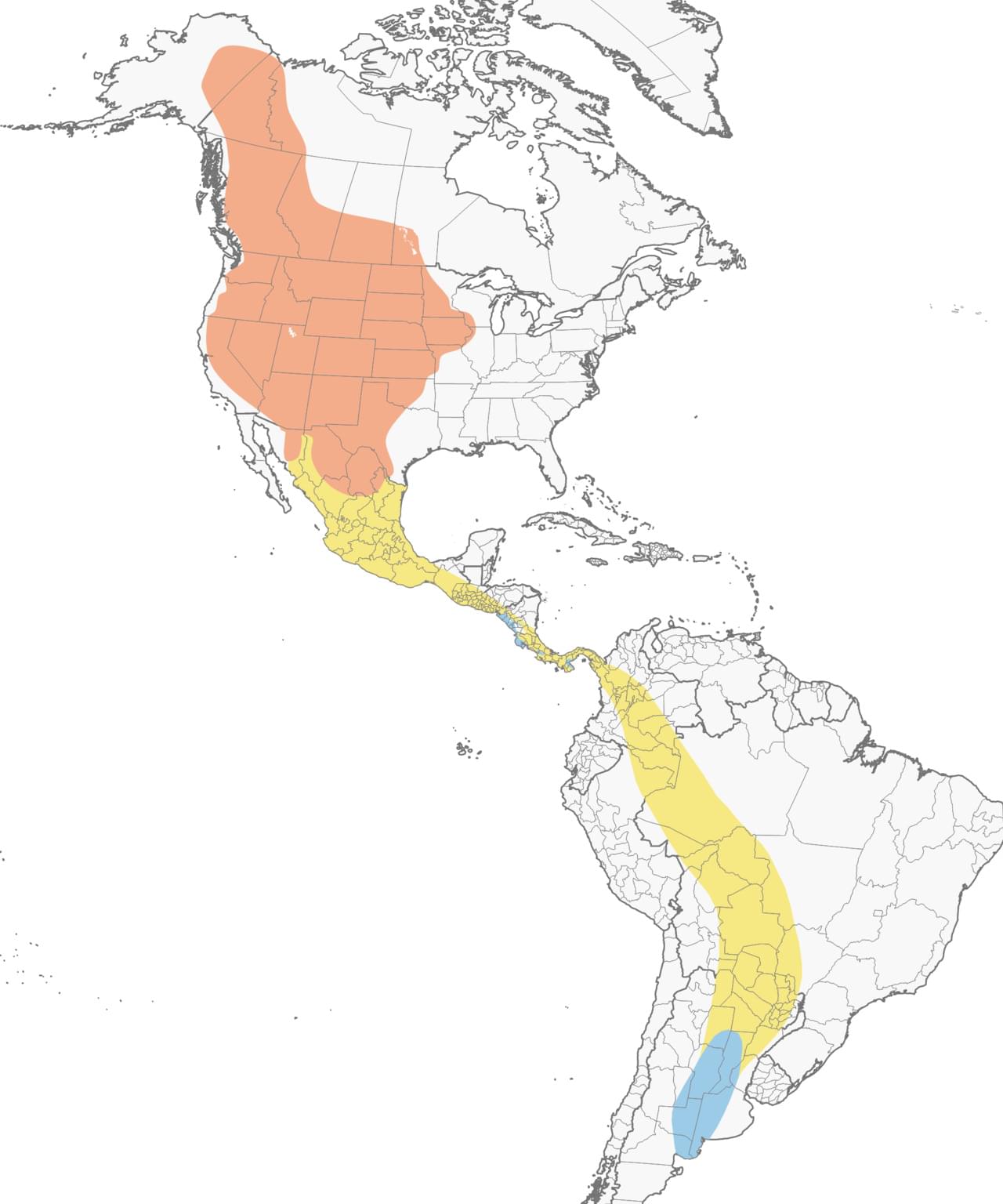

My eyes inevitably turn skyward (and to eBird) as I await the return of my favorite transequatorial migratory species: a brilliant buzzard now known as the Swainson’s Hawk (Buteo swainsoni). These brown-caped raptors undertake one of the world’s greatest journeys, forsaking the open lands of the boreal summer for the strikingly-similar drylands of austral summer. I have a running family joke, chattered through gritted teeth in our brief but bitter winters, that I plan to join them in their eternal pursuit of the sun, but I’m dead-certain neither my conscience nor wallet could handle biannual round-trip flights and a second residence in Córdoba or Salta or La Rioja.

Since first laying eyes on these striking bicolor relatives of the more familiar red-tailed hawk, I’ve shrugged at the name. As a principle, I personally do not believe in applying any human’s name to any other living thing. This belief is only worsened by the legacy of centuries-long colonialism and elitist gate-keeping that often accompanied the human journeys on which these creatures received their common name. I have no personal grudge against the English naturalist, William Swainson, after whom the bird is named, nor Charles Lucien Bonaparte, who did the bestowing. It is simply a matter of principle. Efforts are already underway by the American Ornithological Society to change this passé convention and I won’t belabor this anymore. Today, I only aim to propose a name for my favorite, aforementioned raptor: the Jornada Hawk (Buteo jornada).

Why “Jornada Hawk?” First, the breathy alliteration plays quite nicely. It will take the anglophone community a bit for the Spanish j to stick, but if Americans can order “Baja Blast” at Taco Bell, I think we have a chance.

Second, its preferred environs. This species’ toughness is best demonstrated in New Mexico along the old colonial Camino Real de Tierra Adentro. The Jornada del Muerto, an expansive dusty basin once marked by little more than creosote (Larrea tridentata), now hosts an experimental range conducting over a century of research on dryland management. Most westerners simply know it from the rest stop and historical signs north of Las Cruces on I-25. Jornada Hawks survive here with a broad diet, including the uniquely-adapted creosote grasshopper (Bootettix argentatus): one of the few animals able to tolerate the toxin contained within the creosote plant’s leaves. In South America’s Gran Chaco, Monte Desert, and Dry Pampas regions, southern reflections of our own deserts and grasslands, creosote species of the genus Larrea are more diversified and abundant… and the winter respite of the Jornada Hawk.

Swainson’s Hawk Range [Orange is breeding (northern summer / southern winter), blue is nonbreeding (northern winter / southern summer), and yellow is migratory] © Cornell Lab of Ornithology

But, you protest, the mighty Jornada Hawk occupies far more habitats than simply creosote deserts. You argue that you may have seen them in your favorite Chihuahuan Desert grasslands, like the incomparable Otero Mesa: a window into the pre-colonial past that deserves preservation as a National Monument. You may have seen them on the painstakingly-restored prairies of the American Prairie Reserve or in the coastal California chaparral so famously studied by Michael Soulé. (As an aside, there exists an unstudied hypothesis ready for testing: the Jornada Hawk is responsible for the proliferation of Larrea tridentata after the end of the last Ice Age. Creosote doesn’t appear anywhere in the North American fossil record until roughly 10,600 years ago, after the ice melted. Who do we know that makes a yearly round-trip from the Larrea-covered Southern Hemisphere that could have helped a new species – hidden in its feathers – succeed after a wildfire event, perhaps one similar to the recent blaze in the Texas panhandle larger than the state of Rhode Island? Someone put a graduate student on it!)

I counter those arguments of the hawk’s broad breeding range with the most basal response: the word itself. Jornada means “journey” in Spanish; few animals undertake a jornada quite as amazing as the Jornada Hawk.

But, again, I’m just throwing a hat into the ring. Many names have more merit than the first man who knew somebody that knew somebody. I encourage you to do the same for my beloved Jornada Hawk or your own favorite passerine or squamate or wildflower or anything else. Let’s continue to move beyond biological flag-planting.

Jon Rezendes is a former US Army infantry combat veteran, Ranger Instructor, and graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point. Since leaving service, Jon works for a decarbonization-focused software company and dedicates his life to the preservation of wilderness with his wife, a certified associate wildlife biologist and PhD student, and their two children. In his spare time, Jon is a member of the Board of Directors of the Texas Lobo Coalition and the Frontera Land Alliance. Visit jonrezendes.com to learn more.

I am sorry to see the Rewilding Institute wading into “decolonization” and proposed changes to bird nomenclature. Jon Rezendes does a fine job sidestepping the entire morass, but I suspect an unwitting editor applied the unfortunate title to the article.

I happen to agree with Jon that we have plenty of good options for bird names (and plant names and place names) without resorting to eponymous honorifics.

But, really, why bother? The contention seems to be that the eponyms are offensive to some who might otherwise be bird (or plant or place) advocates. Birds and plants and places certainly need more advocates and defenders, and if changing all their names does the trick, count me in.

Let’s set up a study to see if that actually happens. Did conservation advocacy and spending increase for Thick-billed Longspurs when McCown got the boot? How about Long-tailed Ducks when their unspeakable name was erased? I will note that it didn’t take bird renaming for pressure to be applied to stop the spraying of pesticides in Argentina that decimated Swainson’s Hawks two decades ago.

Is the renaming fad for us or for the birds?