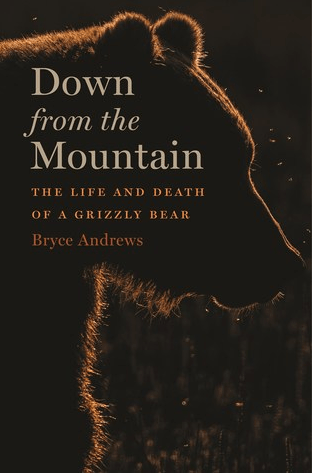

Down from the Mountain: The Life and Death of a Grizzly Bear.

Featured Image: Grizzly © MasterImages

By Bryce Andrews Review by John Miles

Conservation biologist and writer Paula MacKay, in an essay titled “Rewilding Literature: Catalyzing Compassion for Wild Predators through Creative Nonfiction” (in Writing for Animals, Ashland Creek Press, 2018), explains how literature can engender compassion for animals, especially wild predators. Factual accounts of the plight of these animals does not seem to lead to compassion, so what will? She cites carnivore ecologist Christina Eisenberg who has written in her book The Carnivore Way: “Science and environmental law can help us to share landscapes with fierce creatures, but ultimately, coexistence has to do with our human hearts.” MacKay and Eisenberg’s contention that we must find ways to engage the heart came to mind as I to reviewed Bryce Andrews’ wonderful but sad Down from the Mountain.

Bryce tells the story of a grizzly that lived in Montana’s Mission Mountains but was killed as a consequence of being drawn to Mission Valley by an abundance of food there. The valley floor is the location of the Flathead Indian Reservation, though most who live there are not tribal members, another sad tale he summarizes. Bryce describes a fertile valley where the soil had “succored native people and grizzly bears for thousands of years,” but in the early 21st century it is “hidden by roads, power lines, prefabricated ranch-style houses, tilled fields, and uncountable miles of barbwire fence.” The tribe established the Mission Mountains Tribal Wilderness of nearly 92,000 acres in the mountains to the east , but grizzlies living near the valley and deprived of some of their wild upland food like the loss of whitebark pines and their rich nuts to beetle infestations, are drawn to the valley by orchards, cornfields, and careless humans failing to do anything to discourage them.

By Bryce Andrews, Down from the Mountain, The Life and Death of a Grizzly Bear, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019.

After college, Andrews found his way to Montana where he became a ranch hand and ultimately a small rancher. He found it increasingly difficult to take his cattle to slaughter, so sold is share of the ranch. Seeking, as he puts it, “to make amends,” he took a job with People and Carnivores, a small non-profit working “to mitigate the conflicts that arise when ranchers, farmers, hunters, and recreationists share landscapes with large predators.” This work led him to the Mission Valley where just such conflicts were frustrating attempts by tribal biologists and game wardens to protect both abundant grizzlies and valley residents.

He proposed to experiment by building a fence around a 100-acre cornfield near Millie’s Woods, a stand of forest where bears concentrated for their forays into the valley in search of food. This seemed an unlikely solution to him, but research was showing it had potential and he had no better idea. One of these bears was Millie, a large sow with two cubs. Solving the issue of “problem bears” in the Mission Valley was especially important, Bryce thought, because of its location and the large nearby grizzly population. If grizzlies dispersed southward toward the Selway-Bitteroot and Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness areas, once but no longer grizzly country, and carried bad habits learned in Mission Valley, successful repopulation of excellent habitat would be unlikely.

What bears are taught in the Mission Valley is crucial. If they start raiding chicken coups, they will almost certainly be shot for doing so in the years that follow. If they pick up the habit of feeding in cornfields, they will continue to do so in other places and thereby come into conflict with farmers. If they learn to keep to the high country instead, steering clear of humans and their crops, grizzlies are more likely to prosper and survive.

Admitting he likes a challenging project and physical work, Bryce convinces everyone he needs to, including the dairyman whose 100-acre cornfield was dinner for many grizzlies, to support building an electric fence around the cornfield.

He builds the fence, no small task, racing against the arrival of the bears when the corn matures. There are many challenges such as how to prevent the center pivot irrigation system from crushing the fence and allowing the bears in. The fence goes up, he solves problem after problem, and waits to see if it works to keep the bears out. As he recounts the stories of this work, he tells the parallel story of Millie and her cubs.

The bears that came down in August knew every corner and fold of the land, each tree and unfenced garden. They were careful, if not afraid. Though they went nightly among houses, they were very seldom seen.

Millie taught her daughters how to forage in this risky cornucopia. The little bears were compact, pretty creatures. Only a few months old and full of restless energy, the cubs aped their mother’s movements: When she dug in the dirt, they dug, too. When she paused midstride to scent the wind or listen, they stood still.

Coming down from Millie’s Woods, they passed near enough to Schock’s dead pit to sniff the bones. Crossing Hillside Road, Millie and her cubs saw headlights coming, heard rising engine noise, and loped away through the alfalfa growing north of the cornfield.

Millie’s story, informed by research, is the creative nonfiction element of the book where Andrews imagines the life of the grizzlies central to the story.

Ultimately the fence experiment is unsuccessful, some bears getting into the cornfield, one of whom is a wounded Millie whose face is filled with buckshot on one of her foraging expeditions, drawn to elk hides irresponsibly hung all around a cabin. As the effects of her wounds increase, she takes refuge in the cornfield and won’t come out, even as the corn is harvested. Eventually her cubs are captured, and she is shot by the authorities, putting her out of miseries described in some detail by Andrews. Millie’s fate graphically illustrates what is in store for the bears if some way is not found to mitigate the conflicts between them and people in places like this.

Millie’s story is more than that of one bear (really three, because Andrews follows the fate of her cubs, who eventually avoid euthanasia by being placed in a Baltimore zoo, a long way from home.) The moral is that wild creatures will do what they do to survive. They have no choice, but humans have choices, and when they chose not to exercise them and act irresponsibly in bear country, tragedy results. Andrews does not moralize – he does not have to – Millie’s story says it all. This brings me back to Paula MacKay who cites animal behaviorist Mark Bekoff who sees the process of rewilding as “a personal journey and transformative exploration that centers on bringing other animals and their homes, all ecosystems, back into our heart.” Andrews’ takes us on a personal journey, exactly as Bekoff calls for. Down from the Mountain is about conservation and the plight of wild creatures but equally about one man’s deeply felt effort to do as Bekoff prescribes.

MacKay writes that “For too long, storytelling has exploited human fear and misunderstanding of wild predators and their ultimate expense – a legacy perpetuated in today’s popular media. Global threats to large carnivores call for a new body of literature that encourages respect for these animals versus vilification and widespread persecution.” Down from the Mountain is a compelling contribution to this “new body of literature.” Though he only directly encounters Millie in her death, Andrews develops strong empathy for her as he sees her on trail cameras and from a drone over the corn field. Paralleling his personal story with Millie’s ill-fated journey, he understands her plight and those of the other grizzlies in Millie’s Wood in both a rational and emotional way.

Bryce Andrews can write! He can make building a fence interesting and compelling. Grizzly bears in nearby Millie’s Woods and fear that his experiment will fail are always in the back of his mind as he goes about his work. He builds tension into the story as we know Millie will get into fatal trouble but wonder how, and as he worries about the fate of her cubs. He reports on the investigation of who illegally shot Millie and injects a bit of investigative mystery and outrage at the inability of investigators to prove guilt and prosecute the shooter whom he and investigators are sure perpetrated the crime. This bear story and our awareness that many other grizzlies and other wild beings will face the same fate, tugs at the heart as MacKay says rewilding literature of significance must. Hopefully many will read Down from the Mountain and it will grow in them some empathy for the plight of beautiful wild creatures like Millie and motivate action to protect them from her fate.

_________________________

David Brower, then Executive Director of the Sierra Club, gave a talk at Dartmouth College in 1965 on the threat of dams to Grand Canyon National Park. John, a New Hampshire native who had not yet been to the American West, was flabbergasted. “What Can I do?” he asked. Brower handed him a Sierra Club membership application, and he was hooked, his first big conservation issue being establishment of North Cascades National Park.

After grad school at the University of Oregon, John landed in Bellingham, Washington, a month before the park was created. At Western Washington University he was in on the founding of Huxley College of Environmental Studies, teaching environmental education, history, ethics and literature, ultimately serving as dean of the College.

He taught at Huxley for 44 years, climbing and hiking all over the West, especially in the North Cascades, for research and recreation. Author and editor of several books, including Wilderness in National Parks, John served on the board of the National Parks Conservation Association, the Washington Forest Practices Board, and helped found and build the North Cascades Institute.

Retired and now living near Taos, New Mexico, he continues to work for national parks, wilderness, and rewilding the earth.

I thought this was going to discuss Aldo Leopold’s short story from “A Sand County Almanac” called “Escudilla” about the last grizzly bear in the desert southwest. While I love that account, I was presently surprised to read about this new important contribution to the de-vilification literature regarding large predators.