What Dave Said…

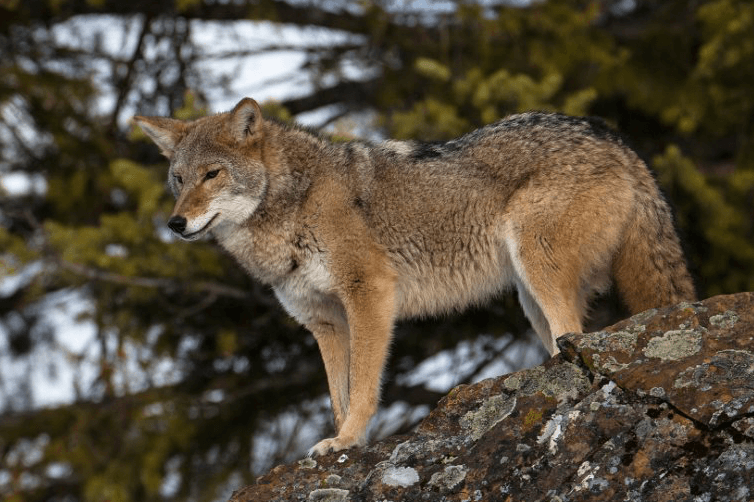

Featured image: Coyote © MasterImages

By Susie O’Keeffe

For those of us who love the wild beings, and want, more than anything, to see their lands and waters returned to them, and their lives to finally be free of the unremitting suffering imposed by human supremacy [1], some days are worse than others.

Last week, I had one of those days.

I woke to the news that Trump’s attack on the Endangered Species Act is official, and that my neighbor is all geared up to start killing coyotes at night. And, of course, there was the daily email barrage describing the suffering and destruction, and accompanied by the pleas for help, support and signatures…

And so, my day began crouched over the computer (on the floor; it’s a long story concerning technology being killed by lightning) furiously typing out a letter to my neighbor who told my other neighbor that my abutting neighbor was gearing up for night hunting.

I never feel like I do enough for the wild beings, and even though I do all I can to protect the land I care for and pay taxes on, I don’t imagine it is going to help much in the long run. A little over a 120 acres of forest, the land was initially cleared for farming, and the regenerating forest was severely cut several times. More recently, large portions of topsoil were scraped off after 50 acres were completely scalped. It is also locked in by roads or connected to land that will eventually see the final crop—house lots. All the same, the wild creatures make the best of it, and I have come to love this recovering forest dearly. So, I let my small community know exactly what I think of night hunting. Here are some excerpts from the letter:

It is proven that coyotes help keep smaller animals, like mice and squirrels, at healthy levels. Since we have destroyed the larger carnivores that help keep the wild community in balance, coyotes help to do so.

Furthermore, it is well documented that when we start killing them, we disrupt their pack structure and they have even more pups, pups who are not taught by their parents to stay away from the cruelest, most destructive animals in existence— humans.

The nighttime is also the only time wild beings can move safely, and meet their needs due to our constant presence, disturbances and noise. Night hunting not only terrifies the coyotes, it also disrupts the other wild creatures, including the birds, most of whom are resting.

In my opinion, the coyotes have as much, if not more, right to exist here than we do. We, who destroy the forests, the animals, and water, and spread our toxins and trash everywhere—so much so that we are now in the process of pushing to extinction a million or more species, destroying the oceans and the climatic system of the planet.

This land here, as with all of the waters and forests of Maine, and elsewhere, has been relentlessly emptied of the wild fecundity and beauty that was rightfully here before Europeans came to exploit, plunder and kill. The thinking behind the idea that we can kill for the pleasure of killing, and that we label certain animals “vermin”, is a way of thinking that was passed to us by our European ancestors, and integrated into every element of our culture. It is a story we continue to adhere to, despite how little of the wild is left, and how much the destruction accelerates every day. We do not have to adhere to this story…

Because of this story, each generation destroys more of every aspect of the natural world. This is a crime against all beings, the planet, and the coming generations. If there is any hope in having a future worth passing on, the thinking that justifies this destruction, and the actions it condones, must end.

A rant. No doubt.

It was not good for neighborly relations, and “send” most likely should not have been pressed. Of course, if humans were slated to suffer as the coyotes, my outcry might have solicited national attention. But, since they are “only coyotes”—animals who have taken the place of wolves in the East as scapegoats for our violence and meanness—most everyone just makes meek, or is indignant that I would dare call out our entrenched behavior for what it is: cruel, and as one neighbor put it, obscene. Eileen Crist says it perfectly: “When wolves or coyotes are called ‘vermin’, however, evil becomes unleashed on the world.”[1]

Today, there was a slight glimmer of light in the news.

Coyote © KIT West Designs

A friend forwarded an article from the Daily Hampshire Gazette concerning a proposed ban of hunting contests for coyotes, and other creatures, toughing it out in Massachusetts. The regulations would make it illegal for a person to “organize, sponsor, promote, conduct, or participate in a hunting contest for coyote, bobcat, red fox, gray fox, weasels, mink, skunk, river otter, muskrat, beaver, fisher, raccoon, and opossum.”

This potential new law is a result of more and more people understanding that to kill and maim other beings for the pleasure of doing so, or for money, is immoral. The fight was unsurprisingly difficult, and victory remains uncertain. Much of Massachusetts Fish and Wildlife’s motivation for considering such a ban comes from the fear that people may start balking at carnivore killing, and this would mean fewer tags, and hence less money. All the same, this small step offers some faint hope in an otherwise exceedingly dark time, and this flicker reminds me of a story a friend told me about the days immediately after Earth First! was dismantled.

My friend will have to remain anonymous as he lives and works in one of the poorest regions in the nation, where being associated with Earth First! could be detrimental to his tireless efforts to restore rivers and streams, protect land, and help poor, marginalized people find work and pride in restoring wild fish passage. His job includes removing dams, providing effective passage, and widening culverts so alewives, blueback herring, shad and other anadromous fish can thrive. His victories are quiet, and growing.

Bushy bearded long before it was fashionable, and quite fond of beverages brewed from hops, my friend has the mischievous twinkle of an Irishman, and a genuineness that evokes ease and trust. The conversation went something like this:

“Oh, so the Earth Firsters! aren’t totally defunct, huh?”

“Yea, Dave started Wildlandsnetwork.org and now Rewilding.org.

“Oh, I’m here because of him.”

“Huh?”

“Well, when it all blew up, Dave said something like, ‘Go to rural communities, that’s where the front lines are now. Integrate. Start helping people get the message that way.’ So, I did. Over the years, people have come to trust me, to see that I am with them, even when I don’t agree with them. They are also seeing that restored streams and rivers are good for them, too. People hate change, so it takes time. I can’t always hold up the banner I have in my heart for the wild, I just do the work day after day.”

Coyote © MasterImages

With things as they are, it’s hard to imagine that a tenacious Irish descendent chipping away in a poor community in the middle of “nowhere”, or a single woman speaking up in rural suburbia where brutalizing the land and creatures is often both business and pleasure for many, can do much good. And maybe, in the end, it won’t. But, all the same, it’s possible that we’re sowing seeds, even if, as in the case of my letter, some of them are duds. We’re moving from our hearts, and some days our hearts are in tatters, and we do not accomplish very much; other days we’re ferocious in our passion to defend the Others, and piss people off, and on a good day we make small gains.

The broader message is that, clearly, Dave was on to something. He was telling us to connect, not simply with the lands, creatures and waters that we love, but also the people, especially that part of pretty much every one that has been thoroughly steeped in the poisonous ideas of our ancestors—the ideas that humans are some how special, and have a God given right to ravage the Earth, and “unravel her poetry”, to paraphrase Eileen Crist.[1] And, as Crist writes in Abundant Earth, we are also asking people to imagine what they have been coerced and sedated into believing is impossible—that a world where wild nature abounds, and humans thrive in reasonable numbersas compassionate members of the life community, is feasible, not to mention, absolutely essential. More often than not it seems inconceivable that we could succeed in getting people to imagine such a world, let alone achieve it.

And so, we each have our coping methods.

My methods are like many. I get out there with the Others as much as I can. I drag their broken bodies out of the roads. I try to tend and help heal the land I have the privilege to care for, protect and learn from. I plant for the buzzing and flapping and stinging creatures. I try to eat as low on the food chain as possible. Sometimes I fly off the handle and rant, and every day I read or listen to a little Buddhist wisdom. Today I read this:

“…sentient beings are as countless as grains of sand in the Ganges. Because they are more than the mind can grasp, the wish to save them all is equally inconceivable. By making such an aspiration, our ordinary, confused mind stretches far beyond its normal capacity; it stretches limitlessly.” [4]

In other words, the healing begins by imagining the unimaginable.

One of the great mysteries of our existence I love to contemplate is the fact that our imaginations appear to be as boundless as the universe. As so many have already written and said, demanding the restoration and rewilding of the planet is also a call to free humanity’s subjugated imagination. It involves understanding ourselves, our cultural history, and especially how we have been taught to project our personal and collective darkness and demons on to the wild beings, especially wolves, and by extension, coyotes.

One of the first Europeans to speak out ardently against human supremacy, and the subsequent greed, cruelty and destructiveness it unleashes, was William Blake. He wrote this about the imagination:

…I know that this world is a world of imagination and vision. I see every thing I paint in this world, but everybody does not see alike. To the eyes of a miser, a guinea is far more beautiful than the Sun, and a bag worn with the use of money has more beautiful proportions than a vine filled with grapes. The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way. Some see nature all ridicule and deformity, and by these, I shall not regulate my proportions; and some scarce see nature at all. But to the eyes of the man of imagination, nature is imagination itself. As a man is, so he sees… [5]

Last night the coyotes sang. They sing less these days, and sometimes I wonder if they are learning to be silent, as they have learned to hunt mostly at night. Their voices could be thought of as one of the last choruses the wild will sing in the East, or an overture to a new era we must imagine into being.

___________________________________

1 Crist, Eileen Abundant Earth: Toward an Ecological Civilization, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2019. On page 3 Eileen defines human supremacy as “the collective, lived belief system that humans are superior to all other life-forms and entitled to use them and their places of livelihood…This worldview makes humanity’s planetary sovereignty appear as a world order that is indisputably given.”

2 I would like to clarify that I am not opposed to hunting for food on a limited basis, and with mindful compassion for the animal. I don’t permit hunting because the creatures desperately need, and have the right to sanctuary, and have virtually none.

3 Crist, Eileen Abundant Earth: Toward an Ecological Civilization, Chicago and London, 2019 p. 30

4 Chodron, Pema, Becoming Bodhisattvas: A Guidebook for Compassionate Action, Shambhala, Boulder, CO 2018, p. 14.

5 https://www.faena.com/aleph/articles/a-letter-from-the-young-william-blake-in-defense-of-the-imagination

Susie O’Keeffe lives at the headwaters of the Sheepscot River in Maine where she is helping degraded land regenerate, and creating a forage forest. She occasionally teaches classes on rewilding and reciprocity at the College of the Atlantic, and works on an independent project entitled, “The Art of Reciprocity”. Susie holds a Master’s of Science with distinction in Environmental Management from Oxford University, England. Fluent in French, her professional experience ranges from comprehensive environmental policy to program creation and direction in the fields of local, organic agriculture and wildlife conservation. Previously Susie worked with a variety of environmental organizations including the Resource Renewal Institute, the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners, and Maine Farmland Trust. Her writing has appeared in Spring: A Journal of Archetype and Culture, Phylogeny, the Spoon River Poetry Review, and The Maine Review. In addition to writing poetry and teaching, Susie is an amateur photographer and gardener. Susie is a member of our Rewilding Leadership Counsel, and is on the board of the Northeast Wilderness Trust.

Thank you for the reminders and for your tireless and mostly thankless efforts toward a better Earth.