#43 Around the Campfire; The Duality of Garden and Wilderness

Wilderness gives wilderness deconstructionists sundry headaches. One of the worst is how wilderness seems to put down living things planted in gardens. If I may toss about a word I loathe, we wilderfolk are thought to privilege trees and other worts planted by wild ecosystems over those planted by Homo sapiens in gardens. We are thus chided for stamping a dualism (always an awful deed) over wildernesses and gardens.

To wit: In 1995, William Cronon wrote

[We must] abandon the dualism that sees the tree in the garden as artificial—completely fallen and unnatural—and the tree in the wilderness as natural—completely pristine and wild. Both trees in some ultimate sense are wild….First of all, I know of no one who says that a garden tree is wholly “fallen and unnatural” and a wilderness tree is thoroughly “pristine and wild.” This is make-believe.

Nonetheless, the trees are unalike down to their roots in dirt and being. To think both are wild is to show a misunderstanding of what wild is. One could also say that a gorilla flinging turds at gawkers from its concrete and steel-bar zoo cage and a gorilla foraging for wild celery with its bunch on the slopes of the Virunga Volcanoes are both “ultimately wild.” Or that a battery hen in a coop so tiny she cannot turn around and a free-flying gyrfalcon in the Brooks Range are both wild.

Here we come to befuddlement between wild and biological. Biology is found in our bodies, in the battery hen, in the garden tree. Biology comes with being alive. Life is biology. Wild splits away from biological in at least two ways. The first is that wild things are free of Man’s will; they are self-willed. They are not in a cage or a zoo cell; neither are they highly bred fruit trees planted by Man in a garden. Second, wildness is the whole wild neighborhood. A mountain lion in the Gila Wilderness is more than itself: it is a tangled bundle with everything near it. A 400-year-old Douglas-fir in an old-growth forest is more than itself since it is caught up with everything about it, from the mycorrhizal fungi in the damp, dank, dark forest floor to the spotted owl in its limbs to the winter rains of the Pacific Northwest. The Doug-fir in the big wildwood is a splinter of a mostly self-willed neighborhood. The garden tree is a sprout in a Man-willed neighborhood. There is an unlikeness—and the unlikeness is wild.

This said, let me acknowledge that I spend time in my backyard of four espaliered apple trees, a peach tree, four cherry trees, a plum tree, an apricot tree, grape vines, daffodils, tulips…a calico cat, a gray tabby, and a fluffy black cat. As I type this, I have dirt under my fingernails from pulling up grass among my tulips and Chama (the calico) is on my lap. Wilderness, no. A garden, yes. Do I like it? You bet I do. But I do not play a mind-game that it is wilderness, nor do I have even an inkling that thanks to it I can live without wilderness. I love my old cats prowling the garden, but I need mountain lions prowling the wilderness, too. Mountain lions cannot live in gardens! Like all my friends, I blend wilderness and civilization in my own life.

But what of wildness and wilderness? Our old Concord teacher, Henry Thoreau, said, “In wildness is the preservation of the world.” True, so true. But a deeper truth is that in Wilderness Areas is the preservation of wildness. Wildness cannot be without land or sea. Wilderness is stead. Self-willed land. The home of wildness. Moreover, in this sad day and age, unwarded wildness likely will not last for long. To keep wildness, we need wild havens (protected areas)—the tougher the better, such as Wilderness Areas.

For indoor thinkers, wildness can be a Platonic abstraction, an “essence” like “treeness,” but wilderness is down to Earth—like big woods and slickrock slots. Wilderness deconstructionists like intellectual abstraction, but they shy from true being; I think they would rather play with essence not hardness. Paul Shepard warned, “The garden is abstracted from the world as a whole.”

And thereby, although alive, it is not wild.

Dave Foreman

Waiting for the first daffodil with my big, old gray tabby friend on my lap

This Campfire is drawn from my forthcoming book, True Wilderness.

Click here to read the original “Campfire.”

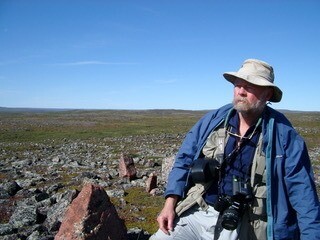

Dave Foreman is the founder of The Rewilding Institute, co-founder of The Wildlands Project and Earth First!, and author of several acclaimed books on wildlands conservation. Books: Rewilding North America | Man Swarm: How Overpopulation Is Killing The WIld World | Take Back Conservation …among several other Rewilding books you can find here. [Photo: Dave Foreman in the barren grounds of Nunavit, Canada © Nancy Morton]