Of Books and Bears: A Review Essay

By John Miles

The bear literature is rich, but with threats to bears proliferating today, writers and photographers are shining their lights on the plight of these charismatic megafauna. Several excellent books about bears have appeared that deserve our attention. Thankfully the news is not all bad, but as I’ve read through these recent publications, a sense of urgency grows – their prospects are not good.

Of the five books to review here, I’ll begin with Bears: The Mighty Grizzlies of the West by Julie Argyle (Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith, 2021). Argyle, a wildlife photographer for forty years with a particular focus on bears, wolves, and wild horses, presents a portfolio of marvelous grizzly bear photos, complemented by scenes of beauty in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. This book is a celebration of these magnificent creatures with many remarkable close-ups, portraits really, of the bears, particularly a female Argyle named Raspberry, a big male designated Grizzly 79, and a male with a misshaped face she calls Snaggletooth. Presented in a 10 by 12-inch format with double page photos and many photo bleeds – a beautifully designed book – the reader, maybe “viewer” would be a more apt term, gets close enough to see the color of the eyes, even facial expressions of her subjects. They swim, scratch their backs, stare into the photographer’s camera from a safe distance, and go about their business of making a living and raising young throughout the Northern Rockies every year.

She salts apt quotations from bear biologists and others throughout the book, an example Mahatma Gandhi’s observation that “If you’re going to be a bear, be a grizzly.” While the book is primarily photographs, Argyle carefully unfurls an essay among them with her thoughts and observations on topics like the grizzly’s relationship with Native Americans, the Endangered Species Act, and hibernation. She clearly loves these animals (she named her business Wild Love Images) and is concerned for their future, but concern is not the emphasis of her essay. She gently advocates for coexistence of bears and humans, and she thinks it is possible. She writes, “Because the human population will continue to expand into traditional grizzly territory, humans will impact where the grizzlies roam. And if the mighty bears are to survive, we must find a way to coexist, acknowledging their needs and giving them the space they require to live.”

While she may be hopeful, Argyle is probably not naïve about the prospects for such coexistence since she has seen the situation of the bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem wax and wane over the decades she has watched them through her viewfinder. Which brings me to the next book, The Grizzly in the Driveway: The Return of Bears to the Crowded American West by Robert Chaney (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2020). Chaney is a Montanan, a science and environment writer for the Missoulian newspaper, and a longtime student of the plight of grizzlies in his home state and elsewhere. Of the bear he writes, “Just knowing such creatures exist keeps many people from feeling safe visiting public lands like Glacier National Park. Yet the presence of grizzlies draws many other people to the same landscape in hopes of experiencing some dream of authentic nature.” He probes how grizzlies can be so loved by some and feared and/or hated by others.

Chaney traces the history of human relations with the grizzlies of the Northern Rockies, summarizing its story from encounters with Lewis and Clark, its systematic eradication along with other predators as the American West was settled, its travails in Yellowstone National Park as its population plummeted in the 1960s and ’70s, its recovery there, and current battles over delisting and hunting. He writes, “Most native wildlife was considered little more than undomesticated groceries by the wagon trains of pioneers departing the East. But the predators fell into a different category: less a resource than an obstacle to be removed. Where grizzlies were concerned, options included baiting, poisoning, dog-chasing, and occasionally using explosives.” The grizzly was listed as a threatened species in 1975 and he notes that the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes were among the first to react by “designating ninety thousand acres of their Flathead Indian Reservation as tribal wilderness.” The tribes banned grizzly hunting and seasonally closed areas where the bears fed. Yet, he notes, not until 2018 did the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee (IGBC) hold a meeting on a reservation. Chaney has a background in political science, and as this point indicates, he plumbs the politics of grizzly protection involving tribes, ranchers, conservationists, lawyers, and politicians.

As a reporter, Chaney has covered all sorts of stories about the bear, from the rare attacks on humans to long meetings of the IGBC and court hearings on the battle over delisting of the bears, some of which he describes. He points out that “Nine out of ten Americans do not hunt, yet the nation’s public wildlife is managed by the 10% who do.” Also, urban Americans generally advocate for conservation of predators while those who live with them mostly want them gone. He asks, “Can the Congressional and social will embodied by the ESA overcome the residents who claim the needs of undomesticated wildlife come second to their right to pursue happiness on private property through economic growth and development?” The problem for grizzlies is that they must live around people, yet need wild places which, he argues, must be preserved. He concludes that “We Homo sapiens have positioned ourselves as the judges of Ursus arctos horribilus’ fate. We must decide why it matters. To determine the fate of the grizzly bear, it must have a worth to weigh.” In this excellent book, Chaney challenges us to ponder the value of the grizzly and, with a clear view of the difficulties of doing so, work to protect it.

Writer and photographer Wayne Lynch takes a different approach in his Bears of the North: A Year Inside Their Worlds (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021). While Chaney’s book examines what might be called the political ecology of grizzlies in the American West, Lynch cleverly and exhaustively presents a trove of information on polar bears, brown bears, and American and Asiatic black bears. Drawing on his forty years of photographing and studying bears, he describes many field experiences and encounters with his subjects while following them through the cycle of the year and explaining what science is revealing about their biology, behavior, and ecology. Lynch organizes the book so that the reader may dive in anywhere and read about an aspect of the bear’s year. Subheadings for April and May, for instance, are “den emergence,” “getting under way,” “hunters on the ice,” “ice cold carcasses,” “more like cows than carnivores,” “droppings and digestibles,” and “catching and carrion.” Later, in the chapter devoted to the fall season, he explains what is known about how the bears bed down for the winter and how they make it through that long northern season. He draws extensively on the latest research, even explaining what DNA analysis is revealing about the relatedness of bears within populations. The northern bears are similar in many ways, and where they are not, he explains the differences.

Information in this work is complemented throughout with Lynch’s terrific photos not only of bears but of where they live, from the American Southeast to the Arctic, and plants and animals who share these places with them. The book is large format with a beautiful layout, the photos complementing the text, the writing non-technical and clear. Short one-page mini-essays are scattered through the book on various topics. One, for instance, is titled “Bark Binging Bears” with a facing page photo illustrating how a hungry Asiatic black bear stripped a large area of bark off a Japanese larch in Nikko National Park, Japan. He explains how and why the bears do this and how this gets them into trouble on tree farms where they can gorge on the cambium of even-age young trees. In the Pacific Northwest, timber companies supplement black bear diets to lessen damage to their plantations. “In western Washington, timber companies place an estimated 800,000 pounds (360,000 kg) of pelletized bear food in feeders annually. Exact amounts are unknown as the information is considered proprietary.” Who knew?

Another short insert titled “The Full Meal Deal,” the facing page photo a full body portrait of a spirit bear, explains macronutrient optimization which is a process by which the bears optimize their diet to meet different nutrient needs throughout the year. Most interesting. The photo caption of the spirit bear, which is a white color phase of black bear found on nearshore islands along the central coast of British Columbia reads, “After finding no salmon, this unwary spirit bear walked directly toward me as I sat by the edge of the stream. I had to yell sternly when it was just 20 ft (6 m) away to keep it from approaching any closer.” An edgy situation, but he got a beautiful photo of this bear.

This is a beautiful, informative, and entertaining book, full of myth-busting insights and entertaining anecdotes. I will share one anecdote here as an example of the remarkable stories a reader will find in Bears of the North.

It was mid-January when biologist Gary Alt located a radio-collared female bear denning inside a concrete drainage culvert that ran under Interstate 84, a major four-lane highway. When Alt checked on the bear, he could hear the cries of newborn cubs. He knew from the topography of the surrounding area that the culvert would flood if it rained or if the remaining snow melted. In either case the cubs would drown. He decided to leave the family where it was for the time being to allow the cubs more time to mature.

On February 2, the weather forecast predicted an inch (2.5 cm) of rain, and Alt knew he could wait no longer. He returned to the culvert to find that the runoff had already begun to trickle through. He tranquilized the mother bear and pulled her and her three cubs out of the den. Alt said that while he was inside the culvert, it rumbled as if a volcano were erupting each time a transport passed overhead. He wondered how the bear family had gotten any rest at all.

Lynch includes two appendices, one on tropical bears, the other on scientific names of the plants and animals in the book, along with extensive references. And while he avows that he doesn’t dwell on threats to bears and other wildlife, he can’t but mention them in a brief concluding chapter titled “The Unbearable Future.” The elephant in the room, he says, is “unrestrained human population growth.” Something must be done about that if the “unbearable future” is to be avoided. This is a book anyone with interest in bears must add to their library.

Bjorn Dihle writes in the introduction to A Shape in the Dark: Living and Dying with Brown Bears (Seattle: Mountaineers Books, 2021) that he grew up in Juneau, Alaska, has traveled extensively in Alaska wilderness, and “… at times I almost hated bears. Like most feelings of hostility, mine were rooted in fear. Yet, there is no place I love more than grizzly country, and no animal has intrigued and challenged me more than the bear.” Dihle encountered his first brown bear when he was four. They were around as he grew up, especially on Admiralty Island not far from his home. Drawn to outdoor adventure from an early age, Dihle read of Lewis and Clark, Hugh Glass, and Jedediah Smith and their grizzly encounters and, like many a young man, wished he could have been a mountain man. These men, he thought, had “possessed a sort of meaning and freedom that evaded my own.”

Most grow out of such romantic notions, but Dihle did not. He decided he would be a modern mountain man, and the place to do it was his home state of Alaska. So, in 2003, he dropped out of college and set off on a month-long journey in the Hayes Range, a place he was told was crawling with grizzles. Things didn’t go well, and he suffered frostbite though had no problems with bears. He was undeterred but was no longer envious of what he began to see as the “brutal and lonesome lives” of the mountain men. Returning to his explorations, he shared the wilderness with many bears. In this memoir, Dihle describes his journey with Alaska brown bears and how, as he said, he at times hated them, feared them, but ultimately came to respect and care deeply about them.

In Part One of his story, he mixes reflections on the history of human-bear relations, on conservation and conservationists like John Muir, Bob Marshall, and Aldo Leopold all of whom influenced his thinking about bears and wilderness, and insights he gains from many mentors he encounters on his bear travels. In an interlude he writes of one of those mentors, Doug Peacock, a damaged Vietnam War veteran who credits grizzlies and wilderness with saving his life after his military service. Dihle writes, “Meriwether Lewis’ ghost still haunts grizzly country, but Peacock acts as a path of hope for the future of people, bears, and wild places.” Inspired by Peacock’s example, he vowed to work for the bears

Part Two describes how, in the decade prior to writing this book, he “really began questioning the nature of our relationship with the animal.” He begins with a seven-hundred-mile solo journey through the Brooks Range where he encounters bears everywhere. His account of that trip is riveting. Here’s a short passage:

My sandal straps broke, and I rigged them with cord, turning them into a burly set of flip-flops. I was constantly immersed in water, sometimes above my waist, so wearing shoes was out of the question. White and red spots appeared on my swollen feet. I dodged bears, usually able to avoid them before they saw me, except on a mountain pass, where a blond bear ran toward me. It stopped at seventy yards, then paralleled my movements for several minutes. It didn’t exhibit any signs of agitation but rather a sort of predatory curiosity. A few days later, I limped down the Alatna River as a large blond male bear with dark legs swaggered in my direction. He became distracted when he blundered into a small group of caribou and his walk became even more exaggerated. I ducked out of view and gave him a wide berth.

Dihle is a good storyteller and fine writer. Over the years he learned much and found ways to pursue his mission, guiding bear watchers and film crews to places on Admiralty Island where they could, to the safe and mutual benefit of both bears and people, observe and learn about these iconic creatures. He has stories to tell, and readers will enjoy traveling with him on his “voyage of discovery” in brown bear country.

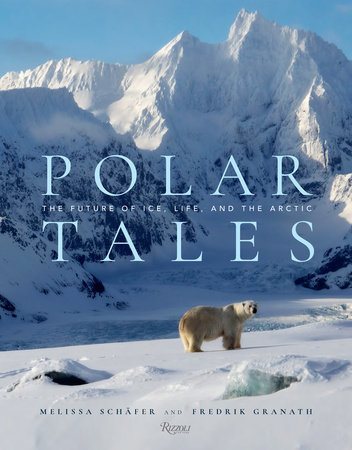

We have been drifting northward in these bear books, and our final book, Polar Tales: The Future of Ice, Life, and the Arctic by Melissa Schäfer and Frederick Granath (New York Rizzoli, 2020) takes us to the high Arctic and the realm of polar bears. Schäfer and Granath are a husband – wife team, she the photographer and he the expert on working in the extreme conditions of filming polar bears in all seasons of the year, especially the winter. He has contributed the text. All the books I have seen published by Rizzoli International Publications have been expensive, large format productions with superb production qualities, and Polar Tales no exception. The text is informative and well-written, and the photography simply spectacular.

The frontispiece features a frontal shot of a polar bear that seems about to climb into the camera, and the facing page offers the following text: “An iceberg the size of a small country breaks loose to become part of the ocean. Glaciers, thousands of years old, melt. Sea levels rise and land disappears. The North Pole pack ice, a seemingly solid island of ice, dissolves into the water. Maps are redrawn. Things that felt eternal are changing.” The book’s theme is set. Photographer and author add in their prologue that their book “is not only about polar bears. It is about all of us. What happens in the Arctic affects all life on our planet.” It is, they add, “about the world we want to leave for the next generation.” With words and photographs, especially with photographs, they take us with them to this world, to Svalbard, at 80° North only 700 miles from the North Pole and a land of many polar bears, when the bears are on land, and to Spitsbergen.

Granath describes the bears as wanderers who prefer ice to land, but which are increasingly forced to spend more of their lives on land like Svalbard. He describes them as unique individuals, drawing portraits of some of them he has come to know well – at least as well as a human can with such a huge predator. He explains how and what they hunt, and Schäfer provides photos of the hunters and the hunted. Life is hard for all. Seals like to birth their pups, which cannot swim until they are two weeks old where they can hide them from predators like the polar bears, but it’s sometimes not possible. Schäfer photographed a cute newborn seal pup lying exposed on the ice. Granath writes, “Arctic life is tough. An hour after this photo was taken, a skinny bear in seemingly poor condition killed the pup and ate it. A little seal pup isn’t much food, but it can be the difference between surviving or not for a starving polar bear. And that is nature in balance. On this ice, life is given, and life is taken.”

Photos and text are complementary throughout the book. Granath writes that the bears are forced to swim more and longer, to their detriment. He describes how researchers in Canada placed collars on 68 adult females and identified fifty long distance swimming events. They learned that adults can safely make long swims, but cubs do not do well. Schäfer captures great shots of swimming bears. Granath writes of polar bear behavior they observe, and Schäfer documents it, especially family behavior. She gets wonderful shorts of cubs playing and interacting with their mothers. Throughout the book, Granath and Schäfer celebrate the power and beauty of the bears they encounter and lament the growing challenges to their survival.

The final section of the book is titled “The Last Stand” and Granath introduces it with an account of a bear they saw on Karl XII Island north of Spitsbergen and Svalbard.

High up on a hillside we spotted a young polar bear, probably three or four years old, trying to catch birds. He was climbing slowly, and he stopped a few times to lay down and rest. He was very skinny. With a long summer and fall void of sea ice ahead, this beautiful bear might not make it.

As he walked out on a ledge and looked at us, the thought of “the last polar bear” struck us. It is something we hope we will never see. But if we do, he will probably look a lot like this one: skinny, climbing a cliff, and fighting for survival.

Why would anyone subject themselves to the challenges of winter expeditions into one of the world’s most extreme climates? A big part of the answer is that they love the adventure, the beauty, and the bears, and fear for their future. Granath writes, “The greatest threat to the future of life on our planet is not politicians with short-sighted agendas or money-hungry big corporations. It is indifference. To quote our dear friend Paul Nicklen, ‘We have to break down walls of apathy.’” They hope that by portraying polar bears and the beauties of the Arctic, they can put a dent in the apathy of people who could never experience them in person. If the incredible photography in Polar Tales cannot make a small dent, nothing will.

Collectively these five books portray a world where the marvels that are bears are threatened by many human-induced changes, from spring hunts for black bears in many US states to global climate change. For all the writers and photographers, a world without bears would be a world severely diminished. They make clear there are no simple answers to how we can assure the survival of bear populations and even of bear species. The polar bear may well be threatened with extinction as their habitat disappears. My journey through these excellent books has taught me much and challenged me to do more wherever I can, certainly for the bears, but for all the life with which we humans share this amazing Earth.

David Brower, then Executive Director of the Sierra Club, gave a talk at Dartmouth College in 1965 on the threat of dams to Grand Canyon National Park. John, a New Hampshire native who had not yet been to the American West, was flabbergasted. “What Can I do?” he asked. Brower handed him a Sierra Club membership application, and he was hooked, his first big conservation issue being establishment of North Cascades National Park.

After grad school at the University of Oregon, John landed in Bellingham, Washington, a month before the park was created. At Western Washington University he was in on the founding of Huxley College of Environmental Studies, teaching environmental education, history, ethics and literature, ultimately serving as dean of the College.

He taught at Huxley for 44 years, climbing and hiking all over the West, especially in the North Cascades, for research and recreation. Author and editor of several books, including Wilderness in National Parks, John served on the board of the National Parks Conservation Association, the Washington Forest Practices Board, and helped found and build the North Cascades Institute.

Retired and now living near Taos, New Mexico, he continues to work for national parks, wilderness, and rewilding the earth.